9. Setting Precedents: New Hampshire's Constitutional History

Located: 1st floor hallway, near the Clerk’s Office

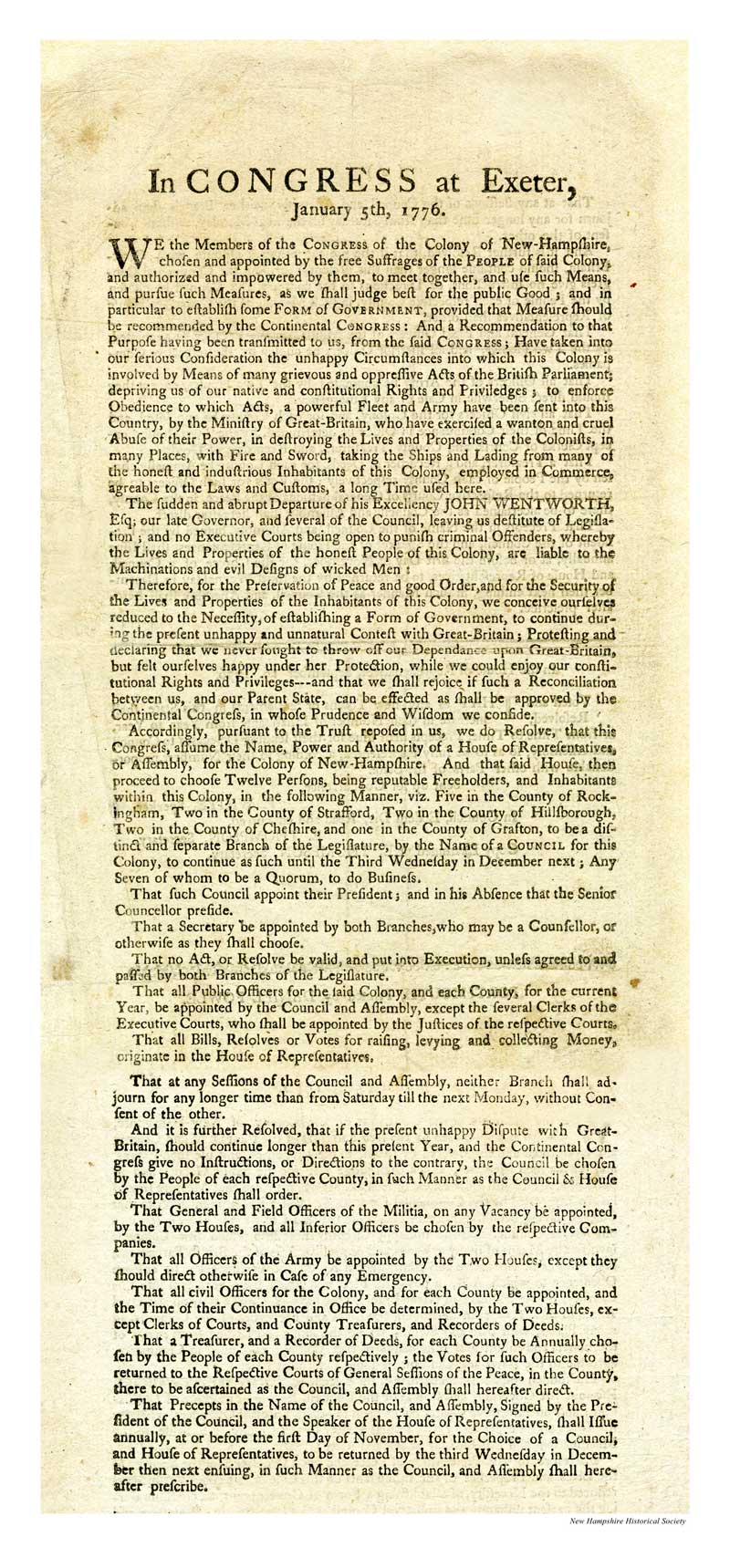

Prints in courthouse exhibit: E.A. Abbey (1852 – 1911) Meeting of Colonists Protesting British Treatment before the American Revolution; New Hampshire’s first Constitution, dated January 5, 1776 (New Hampshire Historical Society)

This E.A. Abbey print vividly illustrates a reality of American politics in 1774 – 1775; for many colonists, the revolutionary spirit was forged in dialogue with their friends and neighbors. Small gatherings afforded an opportunity to air concerns and share ideas for the best response to increasingly offensive British regulation. One essay tells the story of New Hampshire’s first Constitution, enacted before any other state’s, six months prior to America’s Declaration of Independence. A second essay explores the circumstances of the very first constitutional convention ever held, in Concord, New Hampshire, in 1778.

Essays

An American First:

New Hampshire’s Constitution of 1776

New Hampshire was the first American colony to enact a constitution of its own, formally replacing British rule on January 5, 1776. This bold decision was taken six months prior to the American Declaration of Independence, when public opinion across the colonies remained divided between British loyalists, neutralists and revolutionaries. Even the majority of sympathizers to the patriot movement still expected a negotiated reconciliation with Britain. The formation of a new government in New Hampshire signaled an important shift in the expression of colonial claims, from protest and resistance to the actual separation of sovereignty.

The political upheaval that led to this first written constitution in America occurred over a dramatic eighteen months. While an undercurrent of dissatisfaction with the British royal system had long been present in New Hampshire, the province did not harbor widespread radical passions until after Parliament’s enactment of a series of laws (dubbed the “Intolerable Acts” by New England colonists) in the spring of 1774. When Royal Governor John Wentworth dismissed the legislative assembly in June, hoping to thwart its participation in a Continental Congress called for that fall, New Hampshire’s political vanguards defiantly organized a new “provincial congress” that sent two men to the meeting in Philadelphia.

Governor Wentworth’s trepidation about the planned gathering proved apt: The Continental Congress’ Declaration and Resolves (October 14, 1774), a statement of colonial grievances based both on English law and on the “immutable laws of nature,” was eloquently penned by delegate John Sullivan, a well-known Durham lawyer (later to be named New Hampshire’s first Federal Judge.) The idea of individual and collective rights beyond those explicitly granted by proclamation or by English common law, and defined by Parliament, was by now prominent in the dispute with England. A growing consensus in New Hampshire viewed Parliament’s escalating dictates of royal power as “most dangerous and destructive of American rights.”

By December, 1774, when King George III’s decision to ban arms and ammunition exports to America triggered a brazen raid by colonists on Fort William & Mary in New Castle, it was clear that New Hampshire’s Royal Governor was losing his grasp on power. Economic troubles mounted in the spring of 1775, when a colonial boycott against British imports met the punishment of Parliament, which prohibited all trade except with Britain and the British West Indies, and barred all New England ships from North Atlantic fisheries. The unwelcome presence of British warships in Portsmouth Harbor to enforce the New England Restraining Act further fueled the ire of seacoast merchants and residents.

Loyalists to the Crown remained, but the increasing relevance of the patriot cause had redefined the colony. In April, New Hampshire’s patriot militias rallied in response to news of battles in Lexington and Concord, Massachusetts. Thousands of New Hampshire men drilled in Cambridge and Medford through May; and in June, they valiantly shouldered the rebel cause at Bunker Hill. In August, Governor Wentworth, long denied respect by an irascible populace, finally sailed out of Portsmouth Harbor for good.

Absent a Royal Governor, and never having had a written charter, the colony’s assembly, courts, and commissioned officers no longer wielded authority. The extra-legal provincial congress, along with local officers and committees, scrambled to manage the peace, regulate trade, and coordinate the militia.

Leaders in New Hampshire’s provincial congress considered the possibilities for a more sensible and complete solution. While some members pushed the provincial congress to assume the functions of a centralized government, many balked at the idea. Members looked to the Second Continental Congress for “explicit advice respecting the taking up and exercising the powers of civil government.” “The conduct [of] the affairs of this colony [is] at this time … in some confusion,” explained William Whipple in a letter to New Hampshire’s two delegates. “Our present situation is attended with many difficulties,” echoed Meshech Weare, of Hampton Falls, in his own letter to Philadelphia, “[and] we greatly desire some other regulations.”

The radical idea that the thirteen individual “states” should set up their own governments had already been proposed to the Continental Congress by Massachusetts delegate John Adams. However, even as the Continental Congress was now managing a war effort against the mother country, many delegates were not yet committed to the cause of formal independence. Recognizing New Hampshire’s dilemma, in early November, 1775, the Continental Congress issued a carefully worded resolution: “If a full and free representation of the people … think it necessary,” it stated, New Hampshire should “establish a form of government, as in their best judgment will produce the happiness of the people, … during the continuance of the present dispute between Great Britain and the colonies.” It was an historic step: Congress had now officially endorsed the creation of a provincial government based solely on the will of the people.

Congressional Delegates John Langdon and Josiah Bartlett (who replaced John Sullivan when he was appointed a general in the new Continental Army), explained to their New Hampshire compatriots that limiting the recommendation to a temporary government “ease[d] the minds of some few persons who were fearful of independence; we thought it advisable not to oppose that part too much, for once we had taken any sort of government, nothing but negotiation with Great Britain can alter it.” Langdon and Bartlett suggested the formation of a house of representatives and a council (reminiscent of New Hampshire’s colonial assembly, but with no governorship). General John Sullivan, long having advocated self-governance for New Hampshire, sent a letter urging the provincial congress to adopt a formal, written constitution assuring the people’s control. “No danger can arise to a State from giving the people a free and full voice in their own government,” he wrote. He advised that direct and frequent elections should be held, by secret ballot, for all representatives and councilors. He suggested the same for a governorship as long as it carried no absolute veto power. Each “check upon [the] conduct” of officials, Sullivan reasoned, would protect against the abuse of power and further a government that is “instituted for the good of the people.”

New Hampshire’s Fifth Provincial Congress opened in Exeter on December 21, 1775. The formation of a new government was debated, with the resolution of the Continental Congress and the advice of John Langdon, Josiah Bartlett and John Sullivan all considered. The members voted to become a House of Representatives, and assigned a committee to draft “a new constitution.” By January 5, 1776, an independent “Form of Government” was enacted for New Hampshire.

New Hampshire’s first constitution contained just 911 words, about a third of which described the “unhappy circumstances” that brought about such an extraordinary step. Parliament’s “many grievous and oppressive Acts,” along with “the sudden and abrupt departure of his Excellency John Wentworth, Esq., our late Governor,” left the colony no choice but to establish a form of government, the preamble explained. Indeed, without the courts, “the lives and properties of the honest people … [were] liable to the machinations and evil designs of wicked men.” As specified by the Continental Congress, the new constitution would remain in effect only for the duration of the “present unhappy and unnatural contest” with Great Britain. The remaining hope of at least some voting members for an accommodation with Britain was clearly stated (“we shall rejoice if such a reconciliation between us and our parent state can be effected”). Likewise expressed was New Hampshire’s loyalty to the Continental Congress (“in whose prudence and wisdom we confide”). This juxtaposition of sentiment underscored the significance of the enactment: The colonies’ first true break from the sovereign rule of Britain, as astonishing as it was inevitable, was a wholly new concept whose prospects for success were entirely unknown.

The quickly drafted plan called for an elected house and an appointed council, or upper chamber. No governorship was established. If the conflict with Britain were to last one full year, voters in each county would select new councilors. The people would also choose various minor officials. While this new “Form of Civil Government” assured that powers of legislation, taxation and judicial appointments could be exercised, it did not provide for a bill of rights, an independent judiciary, or any separation of powers.

As modest as this first written constitution in America was, it supported a workable “war-years” government for New Hampshire. Moreover, its early enactment served to strengthen the influence of the patriots’ rebellion that would soon lead all thirteen colonies toward American independence.

The World’s First True Constitutional Convention:

June 10, 1778 Concord, New Hampshire

Since New Hampshire’s Constitution of January, 1776, was intended only as a temporary framework, it contained no provision for amendment. Within the same month, the publication and wide distribution of Thomas Paine’s Common Sense, a pamphlet offering “simple facts [and] plain arguments” in favor of American independence, intensified revolutionary fervor through the colonies. By July, the decisive proclamations of America’s Declaration of Independence rendered any expressed desire to reconcile with Britain (such as was written in the preamble to New Hampshire’s first constitution) obsolete.

Further, the governmental structure established by New Hampshire’s earliest constitution was far from popular with the people of the state. Its plan of legislative apportionment required one hundred freeholders per representative, ignoring the autonomy of small, newly incorporated towns to the west. People also criticized the lack of an independent executive and the concentration of power in legislative appointees, many of whom held more than one office. Governance under the terms of the first constitution, which had never been subjected to the peoples’ approval, inflamed political discord across the state.

By early 1778, New Hampshire’s legislative leaders called a convention “for the sole purpose of forming and laying a permanent plan or system of Government for the future happiness and well-being of the good people of this State.” This meeting, held in Concord on June 10, 1778, marked the first time in world history that elected delegates gathered for the sole purpose of drafting a constitution to then be ratified by the people.

The process was both ambitiously democratic and profoundly difficult. Amid a general sense of unease that arose from the ongoing war, unrelenting inflation, and a very real threat of western towns’ secession to Vermont, the draft put forth by the 1778-79 convention offered too few changes from the 1776 plan and was flatly rejected by town meeting voters. Another convention was called in 1781, to remain in session until a constitution was adopted. After three more years and three additional attempts at securing the voters’ approval, a new constitution finally took effect on June 2, 1784.

The Constitution of 1784 remains in effect, although it has been substantially revised over the years. It is the second oldest permanent constitution in the United States (Massachusetts held a constitutional convention in 1779 and adopted its constitution in 1780). Modern facets of New Hampshire’s government date back to 1784, including a comparatively weak governorship (checked by the power of an executive council), a very large state legislature, and a Bill of Rights that comprises the whole of Part 1 of the document.