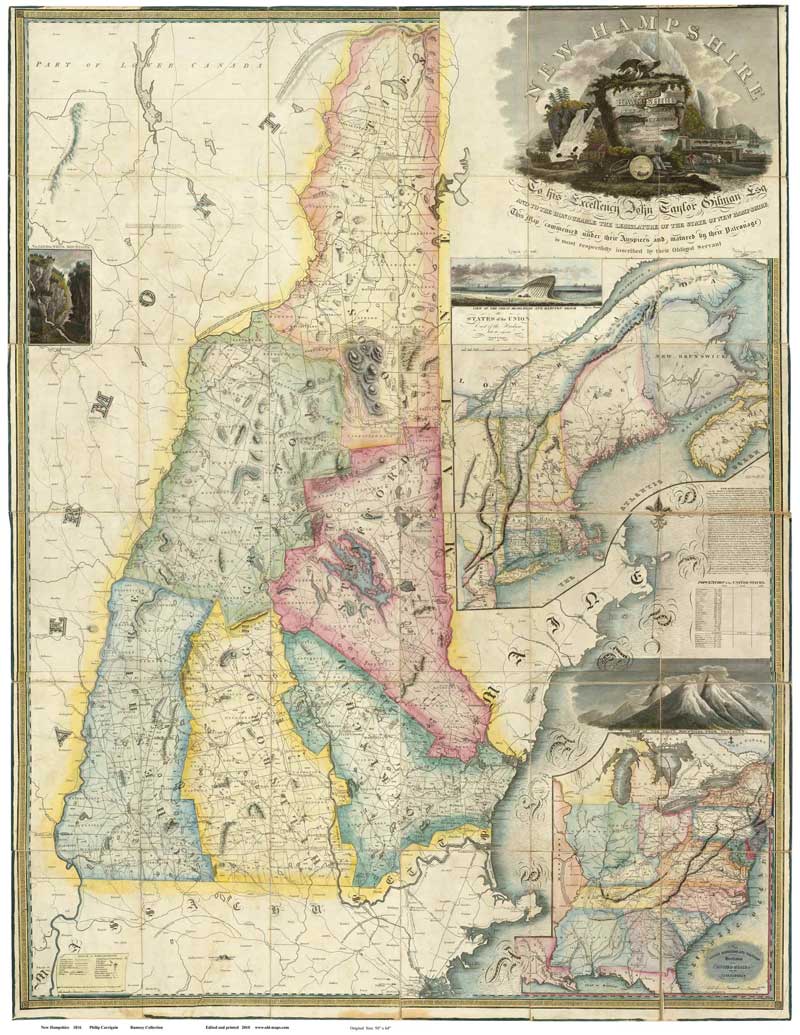

10. The Carrigain Map of New Hampshire, 1816

Located: 1st floor hallway, near the Clerk’s Office

Print in courthouse exhibit: “Map of New Hampshire, 1816” by Philip Carrigain

When Secretary of State Philip Carrigain took on the creation of an official map of the State of New Hampshire, he could not have expected to be tied up with the task for the following ten years. However, the challenge to accurately and artistically record town boundaries, roads, schools, and businesses, as well as land formations, lakes and waterways, and geologic features throughout the state required a comprehensive effort that finally culminated in this glorious map’s unveiling in 1816. The piece is still enjoyed both for its colorful, intriguing presentation and for the breadth of information it provides regarding the era of its publication.

Essays

The Carrigain Map of New Hampshire, 1816

This official state map charts New Hampshire’s developing landscape at a time when most settlements beyond the Piscataqua region and the seat of government in Concord were still remote, isolated and largely self-sufficient. Pinpointing town boundaries, public roads, schools, mills, factories and foundries, this map enhanced opportunities for travel and commerce throughout the state. Rich in detail and impressively accurate, the Carrigain map (named after its creator, Philip Carrigain) was New Hampshire’s primary map for forty years.

The state’s five original counties, Cheshire, Grafton, Hillsborough, Rockingham, and Strafford (established in 1769), along with Coos (1803), colorfully define the map. (New Hampshire’s four other counties had yet to be carved out: Merrimack in 1823, Sullivan in 1827, and Belknap and Carroll in 1840). Many towns have been renamed since the date of the map, and their boundaries reconfigured. Note that two Concords are shown on the map; the one to the west of Franconia became Lisbon in 1824.

The map was drawn in the midst of New England’s “turnpike era,” when the construction of reliable roadways suddenly altered the region’s geographic and economic landscape. Between 1796 and 1893, New Hampshire’s legislature granted charters to eighty-one turnpike companies formed by ambitious private investors for the construction of new public roads. Thirty-two of the roads built under these charters, including the eight that appear on this map, had tollgates and tollhouses charging payment for passage according to a schedule of fees, such as the following:

| Cents per mile | |

| Every ten sheep or hogs | 1 |

| Every ten cattle | 2 |

| Every horse and his rider, or led horse | 1 |

| Every sulkey, chair, or chaise, with one horse and two wheels | 1 ½ |

| Every chariot, coach, stage, wagon, phaeton, or chaise with two horses and four wheels | 3 |

At this same time, river transportation became more prevalent across the United States. The State of New York had begun work on the 363-mile Erie Canal. Many smaller projects, including New Hampshire’s Merrimack River canals between the Massachusetts line and Bow, were newly completed. The map’s narrative mentions plans for future canals that would connect the Merrimack and Connecticut Rivers with New Hampshire lakes including Sunapee, Squam, and “Winnipiseogee.” Soon, however, railroads would transform the business of moving freight and people, rendering these and other plans for more canal systems obsolete.

The Carrigain map captures some of New Hampshire’s natural features, including “Devils Den” (“a noted cave”) in Chester, “the Notch” and “Gap” within ungranted land just south of Bretton Woods, various river falls and rapids, many named bodies of water, and “a view of the Great Boar’s Head and Hampton Beach.” Artists’ illustrations of the state’s mountainous landscape appear as insets on the map, with a title design that grandly boasts of the state’s varied natural resources. Because cartographic work relating to the “mass of granite” comprising the White Mountains was not well developed in 1816, the range is only loosely illustrated. Frank Mountain (now Cannon) and Great Haystack Mountain (now Lafayette) are among the few area mountains cited by name. While the mapmaker offers a “barometrical observation” that the highest White Mountain peak rises to 7,162 feet (874 feet higher than its actual elevation, 6,288 feet), neither its location nor its name, Mount Washington, is indicated.

Probably the most notable natural feature of the White Mountains during the later nineteenth and the twentieth centuries, the Old Man of the Mountain, is also absent from this map. Interestingly, the famous profile’s first sighting was reported by two surveyors engaged in work for the Town of Franconia in 1805, which was the precise time frame when towns were required to perform land surveys for the purpose of this state map. If Carrigain was informed of the discovery prior to the map’s publication in 1816 (well before the site became a tourist attraction), he must not have regarded it as significant enough to mention.

Carrigain’s narratives reveal his perspectives and insights regarding the state. He notes that “industry, morality, and piety,” along with refinement in the arts and sciences, characterize the New Hampshire people. He shares that the ore mined in Franconia “is thought to yield in purity to no other in the world.” He extols the “salubrity of the air,” the “exuberance” of fertile farmland, and “striking and picturesque” scenery. The mapmaker further suggests that New Hampshire “may be called the Switzerland of America,” a characterization that was thereafter often repeated.

It should be noted that the best-known nickname for New Hampshire, “the Granite State,” comes from a poem and song also composed by Carrigain, nine years after his publication of this map.

The Man and His Map

This elaborately detailed and colorful map of New Hampshire reflects more than a decade of exhaustive research and field work conducted by Philip Carrigain, a Concord lawyer who served as the Secretary of State from 1805 to 1809.

Late in 1803, the State legislature required all New Hampshire towns to survey their boundaries, public roads and natural features, intending that the Secretary of State would use the plans to create an official state map. Plans were due in the Secretary of State’s office in June, 1806, and the map’s completion was expected in June, 1807. The process ran into snags and delays almost immediately, as Carrigain applied exacting standards for “the requisite correctness.” He returned at least 130 of the town plans due to “imperfectly described” features or conflicting boundary claims.

Over the next several years, Carrigain, closely assisted by land surveyor Phinehas Merrill, doggedly pieced together the corrected town surveys. Carrigain was determined to complete the map “with perfect accuracy and fidelity,” and spent great amounts of time traveling throughout the state to gather and confirm information. The fact that roads and canals were being newly constructed during this period further complicated this endeavor.

Although the map was not yet finished when Carrigain’s service as Secretary of State ended in 1809, he remained committed to the project’s completion. In 1812, Carrigain’s preparations were complete and he was ready to begin the printing process. As holder of the map’s copyright, he hired copperplate engravers of the finest reputation in Philadelphia, and moved there to personally oversee the intricate engraving and printing processes. Upon the map’s completion in 1816, the State finally received 250 copies for distribution to towns and academies throughout New Hampshire. An undetermined number of copies were also privately sold.