7. Through the Nineteenth Century: New Hampshire's Development of a Diversified and Balanced Economy

Located: 1st floor conference room inside Courtroom A vestibule

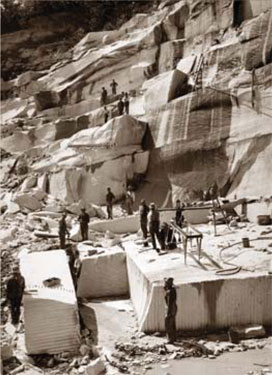

Prints in courthouse exhibit: Harry H. Hicklin, Grist Mill; Lewis Hine, “Mill Girls” photo, Amoskeag Manufacturing Co. (1909); photos of Concord granite quarry and of Connecticut River log drive (c. 1915) (New Hampshire Historical Society)

Additional images of interest: Mill yard photo postcard (1912); Lewis Hine photo of girl looking out mill window (1909); photo of Connecticut River Log Driver (New Hampshire Historical Society)

New systems and methods of manufacturing fueled a surge in New Hampshire’s industrial output throughout the nineteenth century, propelling the state’s textile, granite, and timber businesses to world-renown success. From the mills of Manchester to the forests of the White Mountains, New Hampshire’s culture and landscape were transformed by the ideas and enthusiasm that permeated America’s most modern economy. By the early years of the twentieth century, a recognition of the value of forest protection measures enabled the establishment of the White Mountain National Forest, ensuring the preservation of New Hampshire’s natural beauty.

Through the Nineteenth Century:

New Hampshire’s Development of a Diverse and Balanced Economy

The early decades of the nineteenth century marked a shift in New Hampshire’s economic focus. Portsmouth, like all of New England’s commercial seaports, was severely impacted by trade restrictions designed to protect America’s neutrality during Britain and France’s ongoing wars. At the same time, the state’s agrarian economy and population grew in both scope and importance. The subsistence farming that had sustained isolated settlements in the 1700s gave way to a new, market-based system as turnpikes now stretched inland, easing the transport of agricultural, wood and handcrafted products throughout the region.

The primitive methods and tools used in American mills at the start of the nineteenth century lagged far behind the manufacturing advances that already had brought a factory culture to Western European cities. New Hampshire’s saw mills and grist mills were basic, wooden, riverside structures that provided only a few jobs in each settlement. Even after Eli Whitney’s cotton gin (separating seed from cotton) and Samuel Slater’s automated spinning machinery marked the start of America’s industrial progress, many farm families kept sheep and grew flax for the purpose of spinning their own thread and yarn. The weaving of fabric was a job of precision executed on handlooms. But things were about to change.

In 1812, Bostonian Francis Cabot Lowell returned from a two-year stay in England, where he had carefully studied British power loom technologies for producing woven fabric. He and his partners made some improvements to the processes, and soon opened the first American factory to produce cotton cloth “from bale to bolt” under one roof in Waltham, Massachusetts. The “Boston Associates’” then expanded their holdings in Massachusetts (most notably, at Lowell), as well as in Maine and New Hampshire, including their purchase of a small spinning mill at the swift-flowing Merrimack River’s Amoskeag Falls. With substantial investment and an innovative business plan, the mills they developed at this site would eventually become the largest textile manufacturing complex in the world.

Amoskeag Manufacturing Company

Incorporated in 1831, the Amoskeag Manufacturing Company of Manchester, New Hampshire, like the power loom mills of Lowell, Massachusetts, employed many young women from area farm families. The “Lowell System” established what was considered an ideal work arrangement for young women. Purposefully designed to counter the deplorable conditions of some of Europe’s industrial cities, Amoskeag’s “mill girls”, mostly 15 to 25 years old, resided in chaperoned company boardinghouses with strictly enforced curfews. Workdays were fourteen hours long (later reduced to eleven), but in the young women’s limited leisure time, they were expected to attend church and could take classes and attend concerts. Activities were company-sponsored and alcohol was not permitted. Other New Hampshire textile mills, including the Dover Manufacturing Company, the Nashua Manufacturing Company, and Claremont’s Monadnock Mills, offered similar arrangements for young women workers.

As the number and size of mills increased, so did the demand for labor. Over time, a steady influx of European and French Canadian immigrants found employment in mills throughout New England, spelling the gradual demise of the Lowell System. In this era preceding child labor laws, entire families were frequently employed in various capacities on the mill floor. Manning the machines was dangerous and injuries were common, but the relatively good wages of factory work meant that available jobs were readily filled.

Amoskeag manufactured a variety of products over the years, including steam locomotives and fire engines, sewing machines, Civil War muskets, carbines, and its own machinery, as well as the cotton and woolen fabrics of its fame. The company’s industrial success was complemented by Manchester’s tree-lined canals, wide boulevards, and public parks. Company-sponsored social clubs, recreational facilities, and other benefits engendered the loyalty of employees, who, at the company’s peak in 1915, produced 50 miles of cotton every hour. However, a movement for industrial reform targeting unsafe conditions and long work hours took hold, and by 1918 Amoskeag’s 15,000 employees were unionized.

In the years following World War I, the company’s sales suffered as Europe’s textile industry was rebuilt, clothing styles and fabric preferences changed, and competing mills in southern states gained substantial traction. In 1922, Amoskeag instituted drastic cost-saving measures that were met by a crippling, ten-month long workers’ strike. The company never recovered its renowned manufacturing prowess. After more than one hundred years in business, Amoskeag finally closed its doors in the throes of the Great Depression in 1936.

Sheep, Granite and Timber

Beyond the mills, nineteenth-century New Hampshire experienced booms in sheep farming, granite quarrying, and forestry. The demand for raw wool spiked as new textile mills popped up throughout the region. “Marino madness” swept across the state, as many farmers gave up dairying and grain cultivation in favor of raising sheep. By the late 1830s, seventy percent of the land south of the White Mountains was cleared for pasture (much of it marked by stone walls) and New Hampshire was home to more than half a million sheep. It proved to be a short-lived phenomenon. Within a few short decades, the promise of superior farmland in the Midwest and beyond led hundreds of farmers to abandon their rocky New Hampshire properties and head west.

The quarrying of New Hampshire granite, the state’s namesake natural resource, gradually developed into a valuable industry. Vast reserves of granite on Rattlesnake Hill in Concord were used to construct the state’s Capitol Building in 1816, with much of the excavation and stone shaping labor provided by the inmates of the nearby prison. By 1900, quarries in Mason, Milford, and Concord employed several hundred men.

The heavy and hazardous work produced historic dividends. Huge slabs of granite quarried from the state’s rocky terrain were highly prized in the construction of momentous buildings that would define new cities. More than two thousand railroad cars carried thirty tons of New Hampshire granite to Washington, D.C., for the construction of the Library of Congress. Other nationally-known, historic structures made of New Hampshire granite include Boston’s Quincy Market and First Church of Christ, Scientist, as well as New York City’s Brooklyn Bridge, Tiffany & Company building, and Waldorf-Astoria Hotel.

New manufacturing and rapid urbanization along the Eastern Seaboard fueled a surging demand for timber from New Hampshire’s expansive forests. Paper and pulp mills began to dot the remote landscape. In 1867, the State of New Hampshire sold 172,000 acres of timberland to logging companies that promptly invested in railroad access to the state’s thick, northern forests. Soon, thousands of skilled woodsmen scoured the northern woods, felling massive trees and hauling logs to railroad cars and riverbanks. When there was nothing left to harvest, their camps were dismantled and the lumberjacks, cooks, staff, horses and oxen moved on to the next dense stretch of forest.

Beginning in 1869, annual spring log drives employed the powerful, rushing flow of New Hampshire snow melt to float the loggers’ harvests from northern lakes and rivers to the Connecticut River, and on to sawmills in Southern New England. The 300-mile, five-month-long Connecticut River drive, the largest in America, transported up to 65 million board feet of logs, each thirty to forty feet long. Daring “river drivers” wore spiked boots, carried peaveys, and straddled floating logs to guide the enormous harvest downriver before curious onlookers who gathered to marvel at the sight. Rapids, waterfalls, rocks and bridge piers made occasional log jams, and even drownings, inevitable. Once the record-setting Connecticut River drives ended in 1915, four-foot pulpwood drives continued on smaller New Hampshire rivers for many more years.

The White Mountain National Forest

As passenger rail service gained in popularity, New Hampshire’s fresh air and scenic vistas beckoned more city dwellers to the accessible, impressive White Mountains. New Hampshire’s hoteliers regularly sent their carriages to train depots in a healthy competition for arriving tourists. Many offered luxury accommodations to ease the discomforts of “wilderness excursions” that included trail rides and mountain hikes. Tourism joined textiles and timber as one of the state’s leading industries.

The need to balance competing ecological and economic interests, an oft-cited objective in modern environmental policy, was perfectly illustrated by the interplay of New Hampshire’s major industries near the end of the nineteenth century. The sweeping disappearance of forestland strained both recreational tourism and manufacturing concerns. Numerous large forest fires, many sparked by trains and fueled by piles of logging debris, destroyed views, hiking trails, and even some hotels. The loss of vegetation reduced the soil’s absorbency, and flash floods interrupted mill operations; likewise, low summer water levels deprived their turbines of power. These consequences of unchecked deforestation in New Hampshire and across the country prompted widespread outcries of alarm.

President Theodore Roosevelt’s creation of the United States Forest Service in 1905 advanced a philosophy of proactive management to ensure the future viability of America’s forests. By the time the annual spectacle of Connecticut River log drives had nearly depleted New Hampshire’s largest trees, Congress had passed the Weeks Act (1911), which authorized the federal government to purchase vast tracts of privately-held land for purposes of watershed protection. The establishment of the White Mountain National Forest in 1918 reclaimed over 700,000 acres of New Hampshire wilderness for both public recreation and regulated harvesting. Collaborative efforts of the U.S. Forest Service, private industry, and conservationist groups have since safeguarded the health and productivity of “working forests” in the White Mountains.