6. New Hampshire in the Revolution

Located: 1st floor conference room inside Courtroom A vestibule

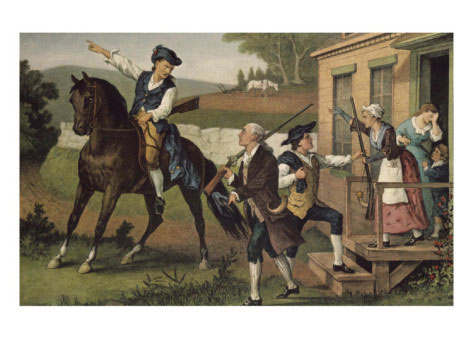

Prints in courthouse exhibit: Currier & Ives, Minutemen of the Revolution, c. 1876; Ken Riley, …the Whites of Their Eyes!, c. 1962; JFK Presidential Library.

New Hampshire played an early and significant role in the opening events of the American Revolution. In December, 1774, the colony’s activists responded to Boston’s express messenger Paul Revere’s warning that British troops sailing toward Portsmouth Harbor were intent on taking the stores of gunpowder and arms from Fort William & Mary. More than 400 New Hampshire men rushed to Portsmouth, prepared to assault the British-guarded fort and remove the munitions before the troops’ arrival. After a skirmish characterized by some historians as the first shots of the Revolution, the rebellious colonists emptied the fort, loading its stores onto gundalows for transport on the Piscataqua River to inland towns for safekeeping. More than a year later, New Hampshire’s independence-minded citizens served with other New Englanders in the siege of Boston and provided more soldiers than any other state at the Battle of Bunker Hill.

Prelude to Revolution

Until the 1760s, colonial America’s governance was largely left to the thirteen individual colonies. While the provinces acknowledged the sovereignty of the British Empire, the British Parliament had no role in levying taxes or fees on this side of the Atlantic. Virtually all of the taxes instituted by the colonies resulted in much smaller tax burdens for American colonists than were paid by the resident citizens of England.

At the end of the Seven Years War in 1763 (most of which was fought on American soil in what is known as the French and Indian War), Parliament instituted a series of direct taxes on the colonies, seeking to recoup some of Great Britain’s substantial war debt. By this time, the many years of colonial autonomy had carved a new and distinct American identity in the minds of the colonists. Provincial legislative assemblies, regular town meetings, and a free press had cultivated the colonists’ interest in issues of policy and their belief that their opinions should matter. Across the colonies, Parliament’s imposition of burdensome taxes and restrictions became a serious source of discontent.

For ten years (1764-1774), the Sugar Act, the Stamp Act, the Townshend Acts and the Coercive Acts met with consistent and stubborn refusals and denunciations by the increasingly united colonists. In 1773, New Hampshire joined other colonies in forming a network of Committees of Correspondence to foster their efficient communication and cooperation. When angry Boston merchants threw forty-six tons of tea in the harbor to protest the tea tax, New Hampshire’s Committee of Correspondence expressed support for the recalcitrance of Boston’s radicals, promising “ever [to] view your interests as our own.” When Royal Governor John Wentworth disbanded the increasingly rebellious legislative assembly in May, 1774, members simply moved their operations from Portsmouth to Exeter, met as the Provincial Congress, and elected representatives to the Continental Congress in Philadelphia. Indeed, the proud and confident mindset of the people who had settled this northernmost colony was a powerful force. It would soon prove instrumental in charting the revolutionary course toward American independence.

The Storming of Fort William & Mary

The colonists had a very limited supply of gunpowder left over from their involvement in the French and Indian War, and had no reserves of saltpeter, a key component in its manufacture. In a move that exacerbated the colonists’ resentment of the monarchy, in September, 1774, British Major General (and Massachusetts’ Governor) Thomas Gage ordered a battalion of redcoats to transfer the substantial store of the “King’s powder” from the Massachusetts Provincial Powder House outside of Boston to British-fortified Castle Island in Boston Harbor. This mission prompted the mobilization of thousands of militiamen from the countryside, who gathered in Cambridge, Massachusetts. No armed conflict immediately ensued, but the climate of mutual distrust between the colonists and the Crown was unmistakable. By late October, the King prohibited all exportation of gunpowder and military stores to American colonists.

Unnerved by these events, New England’s independence-minded citizens worried about the British stockpiling of munitions on Castle Island and their own shortage of gunpowder. In December, 1774, the rumored sailing of warships northward toward Fort William & Mary in New Hampshire’s Portsmouth Harbor spurred Boston’s underground patriot movement to action. Whig activists in Boston tasked silversmith Paul Revere, a vigorous proponent of colonial resistance, with one of his many express courier errands of the era: to urge New Hampshire’s Committee leaders to secure the King’s powder at Fort William & Mary. Early on December 13, 1774, Paul Revere mounted his horse and raced over the thick, frozen slush of carriage roads from Boston to Portsmouth. (This gallop preceded Revere’s more famous midnight ride in advance of the Battles of Lexington and Concord by four months.) By late afternoon he delivered his urgent message to the hastily convened Committee of Correspondence. The Committee immediately decided that the powder stored at the fort should be captured before the British ships’ arrival.

With snow in the air on December 14, a fife and drum parade heralded the spirited arrival in Portsmouth of 400 New Hampshire men defying the Governor’s demand for “Obedience to the Authority of Parliament in all Cases.” They prepared to assault the fort. Seeing the mob approach, the fort’s six British guards hoisted the King’s colors and fired both cannon and small arms – considered by some historians to be the first shots of the war – but they were soon subdued as hundreds of men scaled the walls and stormed inside. With three cheers, the New Hampshire men pulled down the British flag. By the end of the day, 100 barrels of powder were taken from the fort, loaded onto gundalows, and sent up the Piscataqua River for safekeeping.

More than a thousand men from outlying towns arrived in Portsmouth the following day, having received word of Paul Revere’s message. They continued the raid on the King’s fort, removing sixteen cannon and sending a supply of small arms upriver for storage. The powder and munitions were later distributed to local militia units and the Continental Army.

The storming of Fort William & Mary was an organized attack on uniformed troops and property of the King, and constituted open treason, an offense that was punishable by death. Despite the Governor’s proclamation deploring the traitorous acts, the men involved, including well-known New Hampshire patriots John Sullivan and John Langdon, were never arrested. The weight of public opinion was assuredly on the side of the perpetrators, and Governor Wentworth knew that the pursuit of their prosecution would have further stoked their cause.

On to War

The taking of Fort William & Mary’s gunpowder and munitions fueled the rebellious undercurrent of daily life in New Hampshire, whose citizens were no longer mere observers of Boston’s activism. They were proved capable of directly challenging the monarchy. New Hampshire’s patriot militia carried out their regimental drills with renewed purpose, anticipating the coming conflict. Riders prepared for express messenger duty. Some towns designated companies of “minute men,” ready to move “at a minute’s warning.”

When messengers spread word of the April 19, 1775 battles in Lexington and Concord, John Stark rushed from his Amoskeag saw mill to Cambridge, Massachusetts, the headquarters of the new patriot command. By April 23rd, two thousand more New Hampshire men had arrived. Colonel Stark was soon elected to command the First New Hampshire Regiment, backed up by Colonel James Reed’s Third New Hampshire Regiment. Many volunteers also joined the Massachusetts regiment led by Colonel William Prescott, a large part of whose farmland lay within the New Hampshire town of Hollis.

Militia groups from all over New England established camps surrounding Boston, and an American siege of the British-held city was soon in place. As they were denied overland supply routes, the landlocked British troops depended on crops and livestock from coastal island farms. In late May, 1775, Colonel Stark led his troops in a raid of these farms, known as the Battle of Chelsea Creek. Stark’s troops removed livestock and destroyed farms that fed the 6,500 British troops occupying Boston. They also forced the abandonment of the schooner Diana, which had run aground in the shallows of the creek during battle. After looting the ship, Stark’s men set it afire.

Weeks later, New Hampshire men would play a significant role in the Battle of Bunker Hill. When the Americans learned of the British army’s plans to seize and fortify the strategically valuable high ground of Charlestown Heights, they decided to beat them to it. Late on June 16th, Colonel Prescott led more than a thousand men from Massachusetts and Connecticut regiments to Charlestown Peninsula’s Bunker Hill and Breed’s Hill. Working through the night, they constructed a sizable infantry redoubt at the top of Breed’s Hill, with breastwork of dirt and rails, stuffed with hay, running down the east side. After British troops fired shots from the water at dawn, Colonel Stark arrived with reinforcements from the 1st and 3rd New Hampshire regiments, doubling the number of American soldiers already there. Stark took a close look at the colonists’ positions. He ordered his men to extend the breastwork by a three-foot high stone wall down to the beach, shielding the rebels against any attempt to skirt the left flank near the water’s edge. Stark deployed some New Hampshire troops along the rail fence breastwork, and organized others, kneeling in three rows behind the stone wall such that as each row fired, the next could reload under cover. He instructed them not to fire until the redcoats had advanced to a spot that he marked by a stake in the ground, thirty paces in front of the wall.

The British troops attempted the exact flanking maneuver that Stark had anticipated. At close range, Stark and his men assailed the oncoming British soldiers with a constant barrage of musket fire from behind the short stone wall, decimating their numbers and forcing a retreat. The British troops regrouped and advanced toward the breastwork and redoubt, until they were again repelled amid enormous casualties. By the third attack, the defenders of the redoubt on Breed’s Hill were almost out of ammunition. Forced to rely on clubbed muskets, rocks, and hand-to-hand combat, the colonists finally yielded possession of the redoubt. Stark’s men fought on, providing order and cover for the colonists’ difficult and bloody retreat over Bunker Hill. The British suffered 1,054 casualties of officers and regulars in this battle, compared to 450 for the Americans. While the British forces ultimately took the peninsula’s hills, the colonials’ perimeter siege of Boston continued uninterrupted. The rebel forces had earned the respect of the British army, in large part due to the skillful contributions of New Hampshire men at the Battle of Bunker Hill.

The staunch revolutionary spirit of New Hampshire’s patriots was undeniable. Many of the same men who fought at Bunker Hill would go on to serve valiantly throughout the War of Independence. By August, 1775, Governor Wentworth, unable to garner support for his continued authority, relinquished his royal office and left America altogether, bound with other loyalists for Nova Scotia. With no remaining official government, the dye was cast: The northernmost of the thirteen colonies, New Hampshire, became the first to adopt its own Constitution on January 5, 1776.