49. The Bus Rides of Protest: 1947–1961

Located: 3rd floor conference room, behind main hallway exhibit #42 (Civil Rights)

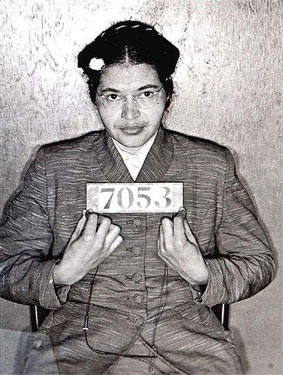

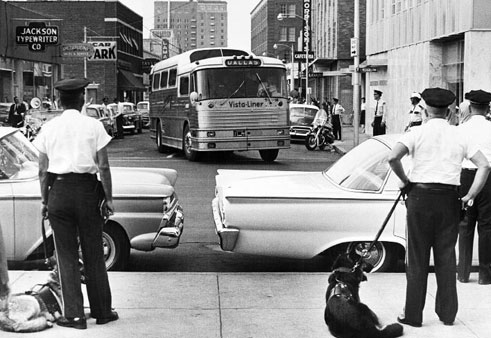

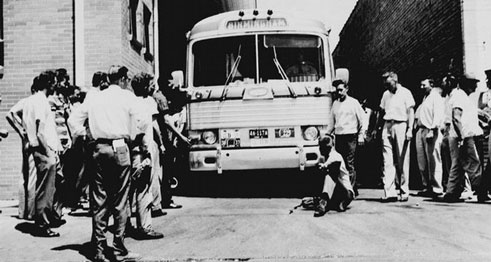

Prints in courthouse exhibit (photos): "Colored" bus terminal waiting room sign; segregated Florida bus passengers; Rosa Parks; Freedom Riders; Freedom Riders bus burning in Anniston, Alabama; Attorney General Robert Kennedy; Freedom Riders bus arriving in Jackson, Mississippi

Other images of interest: more photos of Freedom Riders and bus burning

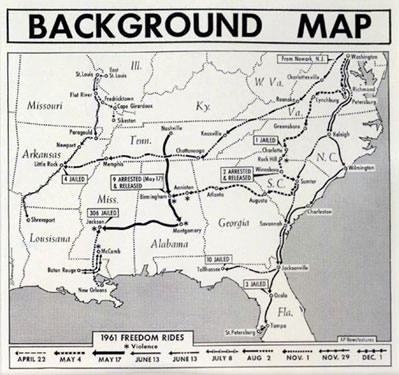

In 1947, the Congress for Racial Equality (CORE) organized racially integrated rides on a commercial buses traveling from Washington, DC to Louisville, Kentucky, to test the effect of a 1946 Supreme Court decision that invalidated segregationist policies in interstate travel. In 1961, the group’s volunteers embarked on a similar bus trip to New Orleans, passing through parts of Georgia, Alabama and Mississippi. On both occasions, black volunteer riders sat in front seats normally reserved for whites, white participants sat in the back, and sometimes they sat together, in violation of state laws and customs. The riders endured bullying and violent reactions of angry locals, as well as arrests and jail time, all while maintaining a purposefully calm posture of nonviolent resistance. Their protests methods proved effective. Both the Journey of Reconciliation and the Freedom Rides garnered national media attention. The widely broadcast spectacle of harsh racism in the Deep South finally forced the implementation of historic federal legal protections for minority citizens using commercial transit.

The Bus Rides of Protest, 1947 – 1961

Constitutional Amendments XIII, XIV, and XV (1865 -1870) abolished slavery and provided citizenship and voting rights for black Americans, giving promise to a new era of racial equality. Despite these milestones, however, fundamental societal change was slow in coming. Federal Reconstruction programs, implemented in 1866 to assist the social and political redevelopment of southern states, were largely resisted and failed altogether by 1877. Southern legislatures enacted restrictive “black codes,” and public facilities, transportation companies, and many private businesses designated separate accommodations for “whites only” and “coloreds.” By the end of the nineteenth century, a court-sanctioned doctrine of "separate but equal" (Plessy v. Ferguson, 1896), perpetuated the distinct racial divide that had long defined life in the American South.

Twentieth-century legal challenges began to chip away at the presumed authority of segregationist policies. However, isolated court rulings had little impact on the systemic culture of discrimination across much of the South. Despite a 1946 Supreme Court decision finding that segregated seating rules for interstate bus travel violated the Interstate Commerce Clause, bus companies continued to separate white and black travelers pursuant to state and local "Jim Crow" laws.

In 1947, the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE) and the Fellowship of Reconciliation recruited sixteen volunteers to travel by bus from Washington, D.C., to Louisville, Kentucky, in a campaign of nonviolent resistance against segregation. On this "Journey of Reconciliation”, black men sat in front seats normally reserved for whites, and white men took seats in the rear. Over the course of the journey through fifteen “upper south” cities, the riders were repeatedly assaulted by police and bystanders, and arrested for violating local laws. As planned, the riders consistently practiced nonviolence. While the campaign pre-dated the era of nightly television newscasts, it was covered by radio and print media, giving publicity to the ongoing plight of black travelers.

Following the landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision that invalidated segregated public schools in 1954, such nonviolent, "direct action" protests became the hallmark of America's civil rights movement. Beginning on December 1, 1955, black citizens staged a year-long, city-wide bus boycott in Montgomery, Alabama, after Rosa Parks was arrested for refusing to give up her seat to a white passenger. Similarly, a seven-month boycott of Tallahassee, Florida’s city buses began in May, 1956, after two young black women were charged with “inciting a riot” by refusing to move from seats next to a white passenger. On December 20, 1956, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Browder v. Gayle that statutes and ordinances requiring racial segregation on Montgomery’s buses violated the due process and equal protection clauses of the 14th Amendment. The boycotts of Montgomery and Tallahassee were triumphantly replaced by integrated seating on city buses.

Persistent and courageous civil rights activism kept the stubborn pervasiveness of racial segregation policies throughout society in the news. Black students across the South held sit-ins at lunch counters and libraries, which CORE and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) soon helped to organize. When the Supreme Court decided that a black student's conviction for trespassing in a "whites only" bus terminal restaurant violated the federal Interstate Commerce Act, CORE once again organized an experiment in inter-racial bus travel, this time following a route into the Deep South.

Like the “Journey of Reconciliation” of 1947, the "Freedom Riders" of 1961 knew they would be viewed by many as agitators forcing a radical agenda. They were trained to expect trouble and to always respond with calm language and behavior. By now, the nonviolent civil rights movement was a formidable political force. CORE leaders believed the Freedom Riders would garner the attention and backing of President John F. Kennedy, who had won the overwhelming support of black voters in the election of 1960.

On May 4, 1961, thirteen Freedom Riders and three journalists boarded Greyhound and Trailways buses in Washington, D.C., bound for New Orleans. They would intentionally defy seating rules and “whites only” bus terminal restrictions as they ventured south. The volunteers rode safely as far as Rock Hill, South Carolina, where three of the riders suffered their first beating by a group of white men at the Greyhound bus terminal.

A violent mob was on hand when the Greyhound bus arrived in Anniston, Alabama four days later. As the bus pulled out of town, the crowd confronted the vehicle, slashing its tires, breaking windows, and tossing a homemade bomb into its interior. Smoke filled the bus, and the rioting mob converged at its door. When a fuel tank exploded, the riders finally escaped through the door and windows, coughing and gasping for air. Several Freedom Riders were brutally attacked by men with clubs and bats while the bus burned.

A similar fate met the Trailways bus with Freedom Riders aboard. In Birmingham, well-known segregationist Police Commissioner Eugene "Bull" Connor had assured the Ku Klux Klan that police would not arrive at the terminal until 15 minutes after the bus pulled in. Approximately 1,000 men, some armed with iron pipes, waited for the bus to arrive. When it did, they freely attacked the Freedom Riders and others who were present, including reporters and photographers.

The Freedom Rides became front-page news, and the Kennedy Administration was pushed to action. Attorney General Robert Kennedy prodded Alabama Governor John Patterson to protect the riders’ further travels through the state. Patterson declined to do so, and refused to talk by telephone with President John F.

Kennedy. Amid reports that segregationists were planning to raid the bus en route to Montgomery, and in view of the Governor’s unwillingness to ensure the riders’ safety, CORE leaders decided to cancel the route. The beleaguered Freedom Riders finally boarded a flight to New Orleans.

Determined students from Fisk University in Nashville were unwilling to accept that racial intolerance and violence had defeated the Freedom Rides. The Nashville Student Movement immediately dispatched new volunteers to Alabama, intent on continuing the Freedom Ride that CORE had reluctantly decided to halt.

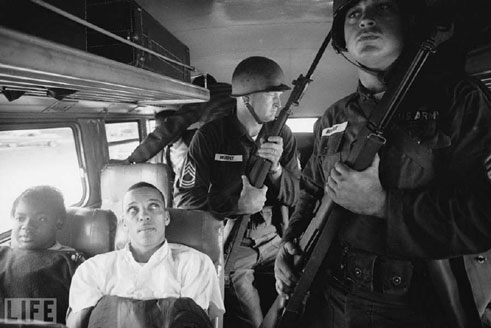

The new riders suffered arrests and assaults in Birmingham and Montgomery. Surrounded by hostile and threatening mobs, these volunteers’ safe passage out of Alabama was finally secured by National Guard escort.

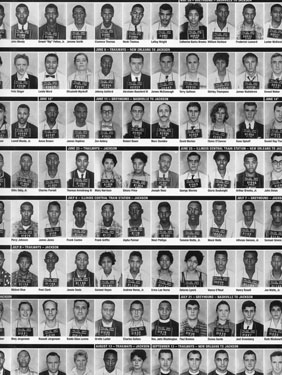

Instead of encountering more violent attacks upon their arrival in Jackson, Mississippi, the Freedom Riders were immediately arrested and jailed for breach of peace and incitement to riot. National media followed the story as more and more activists took buses to Mississippi. Over 300 volunteers arrived to meet the same punishment: imprisonment at the infamous Parchman State Prison Farm. The protesters refused to post bail, purposefully remaining in custody and straining the state’s resources throughout the summer.

In the end, the Freedom Riders succeeded in their mission. At the urging of Attorney General Robert Kennedy, the Interstate Commerce Commission issued regulations prohibiting the racial segregation of bus passengers, effective November 1, 1961. “Jim Crow” signs were removed from transit facilities as bus company policies were revamped to reflect the law. Much desegregation work in the form of protests and legal action would yet be undertaken, but the non-violent bus protests of this period had already proved to be efforts of substantial and historic consequence to America’s civil rights movement.

Colored Waiting Room Sign

Rear of the Bus - (Stan Wayman)

Rosa Parks - Montgomery, Alabama Police Dept

Freedom Riders Map

Freedom Riders bus, 1961 (Mississippi Dept. of Archives and History Museum)

Ride in Anniston, Alabama - AP Photo

RFK on the phone

Escort to Jackson - Life Magazine

Smoking Bus - Birmingham Civil Rights Institute

Freedom Riders - CORBIS

Mug Shot Mural - Multiple Police Departments