48. Civil Rights

Located: 3rd Floor hallway, near Courtroom 5

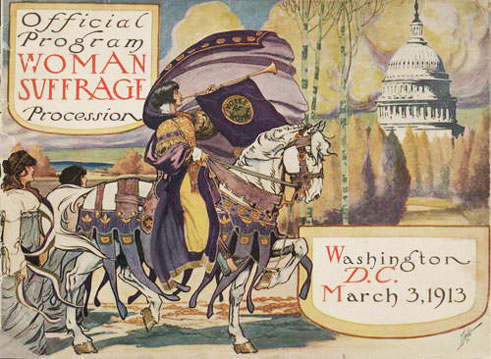

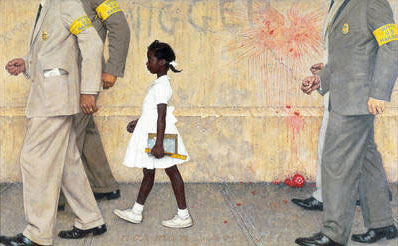

Prints in courthouse display: Official Program, Women’s Suffrage Procession, Washington, D.C., March 1913; Norman Lewis, Woman in Yellow Hat (1936); Norman Rockwell, The Problem We All Live With (1964).

Other images of interest: Women parading in support of voting rights for women, 1917; March on Washington and Martin Luther King, Jr., 1963; photograph of Ruby Bridges

This exhibit examines the nationwide evolution of civil rights for women and African Americans. It details the history of the women’s suffrage movement from its inception in the mid-nineteenth century until the states’ ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920. It also covers important events and legal decisions in the timeline of the civil rights movement propelled by black leaders such as Booker T. Washington, W.E.B. Du Bois, and Martin Luther King, Jr. This review of people and events which defined these campaigns for civil rights, and their ultimate successes in advancing the cause of equality under the law, illuminates the significance of social and political change experienced in the United States, especially during the twentieth century.

Civil Rights Struggles in America, 1848 - 1965

Women’s Suffrage

Seneca Falls and the Birth of a Movement

In 1848, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott organized the first women’s rights convention in Seneca Falls, New York and drafted the movement’s defining document: The Declaration of Rights and Sentiments. Careful to present their grievances of status in an organized, civil, and recognizable style, the founders borrowed heavily from the Declaration of Independence. The initial objective was social and legal equality; suffrage—the right to vote—was a small and seemingly radical component about which even the founders disagreed. After considerable discussion, suffrage was included in the Declaration, and it soon became the movement’s defining goal.

Between 1848 and 1861, suffragists petitioned state legislatures, made speeches, and wrote editorials in attempts to secure women the vote in state elections; however, they met with little success. Other issues dominated the headlines in this era of national tension. When the Civil War ended in 1865, many suffragists assumed that the nation’s new focus on freedom, combined with women’s loyal wartime services, would result in the right to vote. Women, however, would have to wait. Wyoming was the only state to grant women full suffrage by 1869. Additionally, the new constitutional amendments granting rights to freed slaves divided the growing suffrage movement. Many women, including Mott, had long-standing ties to the abolition movement and saw freedom and equality for blacks as a major social victory. They were content to work for suffrage at the state level. Others, such as Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, resented the fact that white women were turned away while blacks went to the polls, and they decided to push hard in Washington for a federal constitutional amendment.

Both groups faced increasingly strong opposition from anti-suffrage groups as the century wound down. These so-called “Antis” believed that the vote would “ruin women and destroy the home” and saw suffrage as interfering with the concerns of men. Society encouraged women to advocate but only for causes that relieved the suffering of the urban poor, working women, and immigrants; voting diminished a woman’s political neutrality and therefore weakened her advocacy. “Anti” propaganda portrayed the suffragists as selfish, unscrupulous women. To strengthen their position against these widespread attacks Mott, Stanton, Anthony, and their followers reunited their forces and formed a coalition of advocacy that could no longer be ignored.

A New World: 1900-1916

At the turn of the century, a new generation of American suffragists took part in the successful British suffragist movement and adopted the approach taken by its radical leader, Emmeline Pankhurst. Mindful of their more conservative American audience, the movement’s young leaders, including Alice Paul and Lucy Burns, decided to bring the campaign for suffrage to the forefront of American society.

On March 13, 1913—the day before Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration—five thousand women walked and rode atop parade floats down Pennsylvania Avenue in the Woman’s Suffrage Procession. The Washington Post predicted that the parade would be “a milestone in the progress of women.” But before the parade had gone ten blocks, the combination of huge inauguration crowds, alcohol, sparse police protection, and apprehension about new evolving gender expectations turned the parade into a riot. The few police officers on the scene declined to protect the suffragists and their children from the angry crowd. One officer insisted that “there would be nothing like this if you would all stay home.” Federal troops eventually arrived to restore order, but not before one hundred women were hospitalized.

Overnight, suffrage was transformed from a quiet special interest cause to a national issue. Paul and Burns, the organizers of the Suffrage Procession, collected donations and lobbied congressional support for a constitutional amendment. Unwilling to abandon the radical tactics learned from Pankhurst, they formed their own separate political group—The National Woman’s Party. Meanwhile, the newly elected leader of the national suffrage movement, Carrie Chapman Catt, launched her “Winning Plan” and campaigned for suffrage in all forty-eight states simultaneously.

Civil Disobedience: 1917-1918

Both suffrage groups had hoped to find themselves a strong ally in President Wilson; however, by 1917 he had done little to acknowledge their cause. He insisted on time to familiarize himself with the movement before deciding whether or not to lend his support. After four unsuccessful years, a desperate Paul picketed the White House—something that had never been attempted by any social advocacy group. On January 10, 1917, members of the National Woman’s Party arrived on Pennsylvania Avenue carrying flags and banners. Two thousand volunteers poured in from across the country; some as young as 19, others as old as 80. They endured inclement weather, condescending and even indifferent behavior from Wilson, and cheers and jeers from the crowds. Every day for almost a year, these “silent sentinels” and their banners could be found on the President’s doorstep.

America’s entry into World War I in April, 1917 had little effect on the National Woman’s Party campaign. Although the nation found it reprehensible to picket a wartime president, Paul refused to abandon her cause. She was adamant that it was unjust for Wilson to fight for democracy abroad while denying it to twenty million women at home. Despite Paul’s convictions, many women did temporarily abandon their cause to contribute to the war effort. By 1918, over 1.6 million American women were employed in wartime industries. But out on Pennsylvania Avenue, new banners taunted “Kaiser Wilson” and reminding passers-by that the Bolsheviks gave Russian women the vote, but American women were still barred from the polls.

On June 22, 1917, the first American women were arrested and imprisoned for “obstructing traffic.” In the following twelve months, two hundred and eighteen women were arrested, with one hundred and six serving prison sentences. The suffragists were, in essence, political prisoners and they were denied the most basic legal rights and privileges. When Congress threatened to adjourn without voting on suffrage, Paul and Burns joined the picket line and were promptly arrested. Congress adjourned anyway.

Two weeks into her sentence, Paul began a hunger-strike—one of Pankhurst’s most effective civil disobedience tactics. Fearing her actions would encourage the other prisoners to do the same, prison officials place Paul in the psychiatric hospital and force-fed her daily through a rubber tube inserted directly into her stomach. On November 15, 1917, more women were arrested. Upon their arrival at the Occoquan Workhouse, they were attacked and beaten by the prison staff. One woman fractured her skull on the stone wall and was knocked unconscious. Her companion suffered a heart attack and died moments later. When Burns tried to determine who had been arrested, she was handcuffed to the ceiling of her cell. Other imprisoned suffragists took up hunger strikes in protest of this inhumane treatment. They, like Paul, were force-fed. When the brutality inflicted during the “Night of Terror” reached the media, suffragists gained immeasurable public support. Within five days, all the women were pardoned and released.

Victory: 1918-1920

It is unclear how large an influence Paul and the National Woman’s Party made on the ultimate passing of the suffrage amendment. Although they picketed and served prison terms, keeping suffrage on the national agenda during wartime and garnering public sympathy, Catt had equal success with her state-by-state campaign. In 1918, New York became the first eastern state to grant women full suffrage: the most significant victory to date.

By 1918, the President and Congress could no longer avoid the issue. Wilson announced his support for a constitutional amendment that would give women the right to vote. In acknowledgement of the contributions woman had made to the war effort, the House of Representatives passed the “Susan B. Anthony” amendment by only one vote in January 1918. Over a year later, in June 1919, the Senate passed the amendment by two votes. From 1919-1920, the state-by-state campaign exploded as suffragists around the country pushed for ratification. In August 1920, Tennessee became the pivotal state, by two votes, to adopt the 19th Amendment: the right of citizens to vote cannot be denied on account of sex. Women, for the first time in American history, were able to directly participate in the government under which they lived as full and equal citizens.

The African American Civil Rights Movement

Short Lived Freedom and the Return of Jim Crow: 1865-1909

Despite the abolishment of slavery in 1865, the Civil Rights Movement (1865-1965) was a century-long fight against an American society that had refused to acknowledge equal rights for blacks. The movement began with Reconstruction-era Constitutional Amendments XIII, XIV, and XV that abolished slavery, provided citizenship, ensured due process and equal protection under the law, and gave black men the right to vote in all state and federal elections. Between 1865 and 1877, these amendments were enforced in the south by the United States military. When the military moved west to attend to territorial conflicts, an overall interest in Reconstruction policies faded and the maintenance of blacks’ rights was left to the individual states.

Unfortunately, racism was a cultural institution in American society that would not be easily uprooted, and black freedom was short-lived. States developed their own interpretations of the rights conferred by the Constitutional Amendments. Soon the rights secured after the Civil War had all but vanished. In Plessy vs. Ferguson (1896), a challenge against Louisiana laws segregating railway cars, the Supreme Court legitimized the doctrine of “separate but equal;” also known as Jim Crow. Many states re-established prohibitions and limitations of the old slave codes. “Colored only” and “Whites only” signs appeared on buses, benches, and drinking fountains and in schools, restaurants, and bathrooms. Poll taxes, literacy tests, and grandfather clauses ensured a low number of black registered voters. Many who did register were verbally and often physically abused. White supremacy groups such as the Ku Klux Klan used vigilantism to enforce Jim Crow.

Toward the end of the nineteenth century, activists such as Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Du Bois renewed the effort to secure freedoms and rights for disenfranchised blacks. Booker T. Washington was a “gradualist” who believed that encouraging black economic development would lead to financial independence. He reasoned that financial freedom would allow blacks to demand corresponding civil and personal liberties. W.E.B Du Bois wanted more immediate results. In 1905, he established the Niagara Movement to secure rights through militant protesting. Lack of funds and poor overall organization disbanded the group, but it was soon replaced by a stronger and more battle-ready one: the NAACP.

Promoting Equality: 1909-1945

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) was established in 1909 to provide political and legal advocacy for full civil rights. By 1919, the NAACP had 90,000 registered members. It established a national headquarters in New York City; an epicenter of African-American advocacy. Marcus Garvey’s “Back to Africa Movement” strongly encouraged racial solidarity and a rebirth of racial and heritage pride. Black communities were coming together in New York’s uptown burrows, many forced there as midtown Manhattan was redeveloped and gentrified. Seven hundred and fifty thousand rural blacks migrated to urban centers, including New York City, looking for work. An unintended consequence of this convergence on Harlem was an artistic explosion—the Harlem Renaissance. From 1910 through the mid-1930s, Langston Hughes, Norman Lewis, Billie Holiday, Louis Armstrong, and Cab Calloway’s new popularity among white Americans helped civil rights activists promote racial tolerance.

While America’s entry into World War I in 1917 could have been another opportunity for racial tolerance, black soldiers were placed in segregated labor units and were often poorly treated, and black officers were frequently disrespected. Instead of returning to the hero’s welcome they deserved, some black soldiers were met with race riots and others were lynched—some still in their uniforms. Even during World War II, according to author Stephen Ambrose, “the world’s greatest democracy [was fighting] the world’s greatest racist, Adolph Hitler, with a segregated army.” But despite the continued inequality on the front lines, the war changed America’s racial relationship with its black population. In 1941, at the urging of civil rights activists, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt integrated wartime industries and two million African-Americans went to work. Another two million joined the federal civil service. War-time jobs opened the way for blacks to experience success derived from economic and social mobility as Booker T. Washington had suggested a half-century before.

Conviction: 1947-1965

By the end of the war, the NAACP was ready to embark on a campaign to desegregate the public school system. Most early attempts at desegregation were unsuccessful; however, in 1954, Thurgood Marshall (the protégée of longtime NAACP lawyer and integrated education advocate Charles H. Hamilton) decided to prove that segregated schools had long-term negative psychological effects on black children as well as violated the Fourteenth Amendment. He secured the services of Dr. Kenneth Clark, a black psychologist, who had previously conducted tests on minority children to determine how segregation affected their self-image. In the landmark case of Brown vs. Board of Education of Topeka (1954), the Supreme Court specifically referenced Dr. Clark’s research and ruled unanimously that “separate but equal” schools were “inherently unequal.” Plessy vs. Ferguson was overturned, and racial segregation of public schools would no longer be sanctioned by law.

Despite the Brown decision, resistance and noncompliance continued, especially in many parts of the South. In some instances, the federal government was forced to use the military to enforce the law. When nine black students were turned away from Little Rock Central High School in Arkansas in 1957, President Eisenhower upheld the Brown ruling by sending in members of the 101st Airborne and the National Guard to force desegregation. In 1960, 6-year-old Ruby Nell Bridges was the first black child to integrate a New Orleans public school. For almost a full year she was escorted each day by four members of the United States Marshal’s Service.

With the success of Brown behind them, the Montgomery Alabama Bus Boycott (1955) was an opportunity for the NAACP to challenge segregation in public transportation. When Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on the public bus to a white passenger, she was arrested. Forty-two thousand members of the black community joined E.D. Nixon of the NAACP to boycott the buses. Local church leaders joined the fight by arranging car pools, reduced taxi fares (in black taxis), and safe walking routes in the face of angry pro-segregation crowds. Most importantly, Nixon and the NAACP called in a relatively unknown young civil rights leader and Baptist preacher from Atlanta to lead the boycott: Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. In June, the Supreme Court agreed that Montgomery’s segregation system deprived people of equal protection under the Fourteenth Amendment. With this ruling, the boycott ended after three hundred and eighty-one days.

Birmingham, Alabama had been a hotbed of racial violence for almost a decade; so much so that it was nicknamed “Bombingham.” Between 1955 and 1961 there were eighteen unsolved bombings in black neighborhoods alone. In 1963, Dr. King and members for the Southern Christian Leadership Council (SCLC) arrived to aid in the fight for political equality in Alabama. They organized numerous non-violent demonstrations; however, dozens of participants, including Dr. King, were arrested and imprisoned. To keep the movement moving forward (knowing that most black families could ill afford to have their primary wage earner imprisoned), students from local colleges, high schools, and even grade schools were recruited to march and gathered in Kelly Ingram Park. Armed with fearless optimism and boundless energy, Birmingham’s children took to the street. After three hours, over nine hundred sat in Birmingham jails. When one thousand more turned out the following day, Birmingham’s Chief of Police Eugene “Bull” Connor brought firefighters and the city’s canine unit to force them back. Those who refused to turn around were set upon by dogs and hit with 10,000 psi (pounds per square inch) of freezing cold water from high-pressure fire hoses. The unprecedented police brutality against innocent people, especially children, increasingly alarmed the public audience and sympathy for the movement grew exponentially.

Never was the sympathy more obvious than in August, 1963 when 200,000 people joined the SCLC in their March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. On the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, King delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” speech which encouraged the assembled men and women to “rise from the dark and desolate path of segregation to the sunlit path of racial justice.” He reminded them to “conduct our struggle on the highest plane of dignity and discipline… [and not to] degenerate into physical violence.” To the immense interracial mass before him he intoned: “I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal.’” When the swell of cheers rose, the movement was forever changed. King’s speech was featured on every television network’s evening news and transcribed in the next morning’s papers. All eyes were fixed on the racial tensions and violence that predominated in the South but affected the entire country. Despite the positive response to the movement from the American public after the March on Washington, less than a month later the 16th Street Baptist Church—the official headquarters for the Birmingham Civil Rights Movement—was bombed during Sunday school. Four young girls were killed and another eleven injured. America was now even more convinced that civil rights were long overdue.

In response to the civil rights movement and increasing racial violence, politicians in Washington were compelled to act. In 1963, in a nationally televised address, President John F. Kennedy urged the country to take action to guarantee equal treatment of every American, regardless of race. Soon after, he advocated for new comprehensive civil rights legislation that would ensure minority voting rights and the integration of public accommodations and schools. The bill was near passage in Congress when Kennedy was assassinated. The following year, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed that bill into law, which became known as the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The next year he signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which prohibited discriminatory voting practices such as literacy tests, poll taxes, and grandfather clauses. The right to vote provided African Americans the opportunity to play an active role in changing the nation’s outdated racial ideologies.

“Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” ~Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Letter from a Birmingham Jail, 1963