25. The Electoral College

Located:

1st floor hallway near Courthouse and Federal Building link

Images in courthouse exhibit:

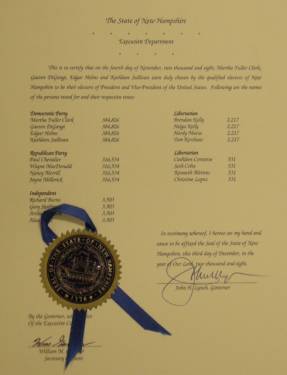

New Hampshire's 2008 Electoral Certificates

The origin of America's unique electoral system for choosing the president dates back to the Constitutional Convention. Through centuries of growth and modernization of the nation's industrial, social and political landscapes, the electoral college system has changed very little from its inception. This essay provides an overview of its history and functionality.

The Electoral College

One of the most vexing questions presented to the delegates at the Constitutional Convention was how to select the President of the United States. Ideally, the president needed to be a respected leader of national standing in order to ensure his ability to govern a large and diverse nation. The delegates discussed whether Congress should choose the president, but rejected the idea as tilting the intended balance of power between the branches of government too strongly in favor of the legislative branch. They debated having the state legislatures choose the president, but feared an undermining of the chief executive’s independence if he was beholden to certain states. The delegates also considered holding a direct popular election for the president; but timely, meaningful communication between voters in thirteen states stretched along 1,000 miles of the Atlantic seaboard was impossible in 1787. As such, the electorate would likely vote for regional favorites, making a majority vote across the country unattainable.

Ultimately, the delegates decided on yet another representative system: A small number of electors from each state would cast votes for the president. Like the compromise already in place for congressional apportionment, the electoral system was designed to satisfy the interests of both small and large states. Each state would have two electors (as each has two United States senators) as well as additional electors depending on its population (equal to its membership in the House of Representatives).

The founders intended that the most knowledgeable and informed citizens, expressly excluding members of Congress and employees of the national government, would be chosen as electors. These individuals would cast votes for their top two choices for president, with at least one hailing from a home state other than their own. The candidate who received the majority of votes totaling more than half of the electors would become the president; the runner-up would be the vice president. In the event of a tie, the House of Representatives would select the president.

The electoral process hit a few snags with the unanticipated, early emergence of political parties. In 1796, the "vote for two" requirement resulted in an awkward four-year term with President John Adams, a Federalist, and Vice President Thomas Jefferson, a Democrat-Republican, in office together. A further complication arose in 1800, when Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr were candidates from the same party running for president and vice president, respectively. While the Constitution allowed electors two votes, it did not distinguish between a vote for president or vice president. Because each elector who voted for Jefferson also voted for Burr, and all votes cast technically counted as a vote for president, the two wound up in a tie, throwing the contest to the House of Representatives. Thirty-six ballots later, after what many surmised was a political deal brokered by Federalist Alexander Hamilton, Thomas Jefferson finally won. Recognizing the flaws of the system, Congress re-wrote the rules to require separate electoral votes for president and vice president, which took effect as the Twelfth Amendment in 1804. (That same year, Aaron Burr challenged Alexander Hamilton to a duel, which Hamilton did not survive.)

In 1845, Congress set a single date for all states to select their presidential electors: "The Tuesday following the first Monday in November, in years divided by four." On what is now known across the country as Election Day, when citizens in each state and the District of Columbia vote for president, they are actually casting a vote for the slate of electors who represent their presidential choice. The winner of a majority of all the states’ electoral votes becomes President of the United States. In mid-December, all the electors meet in their own states to cast their formal votes for president. These votes are then certified and delivered to the President of the Senate (Vice President of the United States), the Archivist of the United States, each state’s Secretary of State, and the Chief Judge for the Federal District Court located where each state’s electors meet. In the event that any state’s certification of votes is not received in Washington, D.C. by the fourth Wednesday in December, a special messenger would be sent to the district judge holding such certificate, who would “forthwith transmit that list by the hand of such messenger to the seat of government.” (Copies of New Hampshire’s 2008 Electoral Certificates, received and held for safekeeping by this court, are displayed here.)

America's indirect presidential election is sometimes criticized as an onerous process that can defy the popular will of the people. In fact, the electoral vote count has differed from the popular vote count on four occasions. Defenders of the electoral college system maintain that it requires candidates to appeal to a widespread and diverse national electorate, rather than focusing exclusively on the most populated urban areas of the country. It is likely that the long-standing debate over this unique blend of democracy and federalism will rage on for years to come.