24. The Vote of the People

Located: 1st floor hallway near Courthouse and Federal Building link

Print in courthouse exhibit: George Caleb Bingham, The County Election (1852)

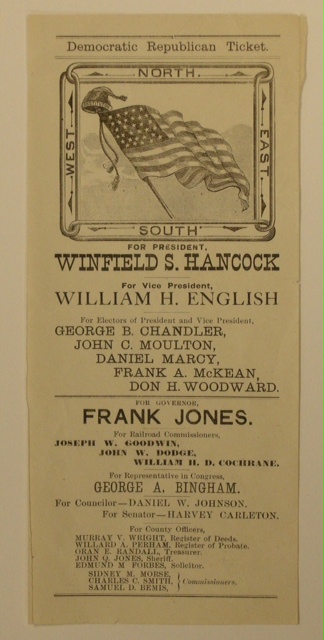

Other images of interest: Patriotic flag banner, c. 1900; Democratic Republican ticket, printed for use in New Hampshire, 1880

There is no more fundamental element to American democracy as the vote of the people. Over time, aspects of the American vote have evolved, reflecting the country’s changing politics, demographics and culture. This essay uncovers some of the history of this essential democratic exercise, since the founding of the nation.

The Vote of the People

The Declaration of Independence announced to the world a new tenet for governmental legitimacy. In order to secure the people’s “unalienable rights,” it boldly insisted that the union of American states would derive all power from “the consent of the governed.”

Eleven years later, in 1787, the Declaration’s appeal for a democratic design surely inspired the delegates attending the Grand Convention at Philadelphia. However, these were learned men – esteemed leaders in their communities – whose familiarity with both colonial and revolutionary American government instilled caution over idealism in establishing a new political system. Unlimited power in the hands of a majority of decision-makers was equated with unlimited power in the hands of a monarch. Intent on protecting the infant nation from the “turbulence and weakness of unruly passion,” none believed that the cause of freedom from tyranny would be served by an unrestrained democracy.

After much deliberation, the framers of our Constitution devised a governmental structure resting on, but restricting the reach of, majority rule. This philosophical approach is reflected in the methods they prescribed for filling the offices of the Executive, Congressional and Judicial branches. Popularly elected state legislatures could decide the manner for selecting “electors,” who in turn would vote for the President. (In most states, the legislature itself selected presidential electors, without a vote by the people.) State legislatures would also select each state’s two Senators. As for the Judiciary, the President would appoint federal Supreme Court justices, for life terms. The only national office holders to be directly elected by the people were each state’s members in the House of Representatives.

The framers of the Constitution left voter eligibility up to the states, which, with the exception of New Hampshire, initially held onto colonial-era property qualifications for voting. New Hampshire’s 1784 constitution had eliminated the state’s requirement for voters to own real estate worth at least fifty pounds. Following the Convention, other states took similar action, so that by the end of President Washington’s second term, ten out of fifteen states had either very minor property requirements or none at all.

Distanced from the workings of the American government, the public’s interest and involvement in the first thirty years of national elections was generally low. In time, however, as roads and canals improved the distribution of news and commerce, the public became more engaged in issues such as western expansion and developing markets. An economic collapse known as the “Panic of 1819” further boosted citizens’ awareness of the impact of national policy decisions on their lives.

Democracy took a substantial leap forward in the 1820s when 18 of the 24 states scheduled popular votes in the presidential election. Although there was just one political party in 1824, four contenders vied to become the first non-Founding Father president. When no one achieved a majority of the states’ electoral votes, the House of Representatives selected John Quincy Adams as President. War hero and “friend of the common man” Andrew Jackson, whose plurality of both popular and electoral votes failed to sway the House’s decision, fired off charges of corruption and launched his second campaign for the presidency. A movement known as “Jacksonian Democracy,” featuring a larger and more enthusiastic voting public than ever before, propelled Jackson into office in 1828. This time, all but two states held popular votes for the race.

The 1830s saw new parties emerge to give voice to variances of opinion, and voter turnout skyrocketed. With a strong two-party system in place by 1840, nearly 80% of eligible voters cast votes on Election Day. Politicking had become something of a sport, with mud-slinging and scandalous rumors about candidates widely reported by an active and partisan press. Parties plied voters with “treats” - most often alcohol – at campaign events and even at the polls. Voting places were filled with boisterous crowds of men sharing and reconsidering partisan opinion, some of whom were ready to sell their votes to the highest bidder.

The fervor spilled over to state and local contests as well. By the mid-nineteenth century, most states held direct popular votes for governor. Party organization produced committed loyalists who went to extremes to secure every available vote. In one especially bitter New Hampshire election, an anti-slavery proponent complained in 1846, “Hell itself could not have belched up so miserable, so degraded a group of drunken vagabonds” as those who were rounded up and led to the ballot box by future President Franklin Pierce. Elections at this time in America’s history were raucous and quite unregulated.

The expansion of democracy from the early to mid-nineteenth century transformed the very nature of the nation’s politics and society. Parties organized and targeted their campaigns to an increasingly interested and powerful electorate, from all walks of life. While the achievement of racial and gender equality in voting rights remained a long way off, “the people’s vote” had become the essential and consequential focus of the nation’s leaders. The core principle of the Declaration, that this government shall exist by consent of the people, was forging ahead.

For information on the furtherance of voting rights, see our exhibit on America’s Civil Rights Movement (1865-1965) outside Courtroom 5 on the third floor of this courthouse.

About the Painting

George Caleb Bingham (1811-1879)

The County Election, 1851-52

Oil on canvas (35 7/8 in. x 48 3/4 in.); St. Louis Art Museum

George Caleb Bingham’s 1852 painting, The County Election, aptly conveys the liveliness and imperfections of the democratic process of his day. White male citizens gather before a polling place to discuss, consider and cast their votes. While most figures in the crowded voting scene display a serious attitude about the franchise, others present a stark contrast. To the side of the crowd, a laughing man is served hard cider by a non-voting African American. One inebriated man is being carried toward the line of waiting voters. A hopeful candidate campaigns just a few feet from the official who takes a voice vote, apparently recorded by a worker on the porch.

The depiction of two men playing a betting game serves as a metaphor for electoral politics in an age when negotiating one’s vote was not uncommon. One figure, bandaged and slumped over in a chair as if just having been beaten, evokes the painful losses of hardscrabble politics.

The artist presented this painting for a national audience, intending it to illustrate the celebrated but sometimes sullied exercise of “the will of the people” in the mid-nineteenth century.