22. Presidential Nomination

Located: 1st floor hallway near Courthouse and Federal Building link

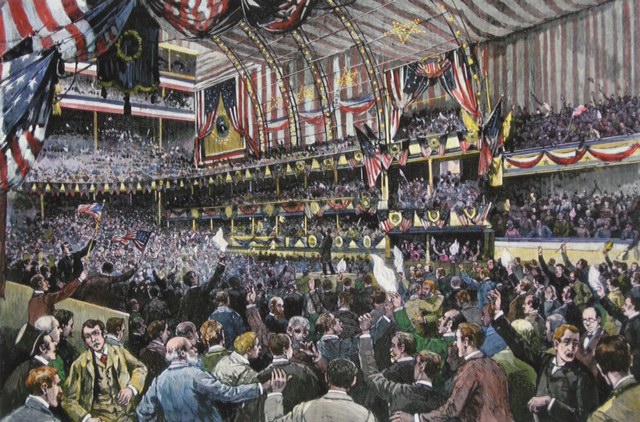

Prints in courthouse exhibit: Republican Nominating Convention, Chicago 1888

Ever since President George Washington's uncontested election to two terms in office, the suitability and selection of candidates for each successive chief executive has been the subject of intense scrutiny. In the early 1800s, presidential candidates were chosen in closed-door meetings of each party's congressional caucus. As the country matured, a sweeping democratization of American politics led to new parties and a surge in political participation. With increasing attention paid to the opinions of the "common man," the Anti-Masons, National Republicans, Democrats and Whigs all began holding national nominating conventions prior to the presidential election. The first national convention for the Democratic Party took place in 1832, with the modern Republican Party following suit in 1856.

The Presidential Nomination

Ever since President George Washington's uncontested election to two terms in office, the suitability and selection of candidates for each successive chief executive has been the subject of intense scrutiny. In the early 1800s, presidential candidates were chosen in closed-door meetings of each party's congressional caucus. As the country matured, a sweeping democratization of American politics led to new parties and a surge in political participation. With increasing attention paid to the opinions of the "common man," the Anti-Masons, National Republicans, Democrats and Whigs all began holding national nominating conventions prior to the presidential election. The first national convention for the Democratic Party took place in 1832, with the modern Republican Party following suit in 1856.

Delegates to these national nominating conventions were typically selected in caucuses of party members, held at the county and state levels. The national conventions were often exciting and suspenseful, with unpledged delegates debating potential candidates for days on end before finally settling on a nominee. For example, New Hampshire native Franklin Pierce's "dark horse" nomination in 1852 came on the 49th ballot, five full days into the Democratic National Convention, as a compromise solution to persistent disputes between delegates over the issue of slavery.

As the century progressed, politically minded American voters began clamoring for reforms to a system that allowed affluent and powerful party "bosses" to wield overwhelming influence over caucuses, delegates and candidates. Seeking a truer measure of public opinion as the foundation of each party's convention and choice of a nominee, as many as twenty states replaced party caucuses with secret ballot primary elections between 1912 and 1920. Due to high administrative costs and low voter turnout, however, most states soon reversed course, once again leaving the selection of national party convention delegates to party-run caucuses. Just a dozen states continued to hold presidential primaries from 1936 until 1968.

New Hampshire held its first official presidential primary in 1916, and its claim as the "first in the nation" primary state dates back to 1920. The import of the state's premier position was not fully appreciated until 1952, the first year that New Hampshire voters could choose a presidential candidate by name rather than simply casting votes for delegates. In that year, incumbent President Harry Truman's defeat in New Hampshire's Democratic primary was soon followed by his withdrawal from the race; and General Dwight D. Eisenhower's unexpected win in the state's Republican primary propelled him toward the eventual nomination. In every election year since, presidential aspirants have converged on New Hampshire with a solid understanding of the first held primary's potential for boosting their momentum and prospects for success. National media coverage of prolonged campaigns attempting to woo New Hampshire's electorate, well reputed as both independent and knowledgeable, has only furthered the significant impact of this small state's primary elections.

Regardless of the excitement that such primary elections generated, through 1968 the great majority of national convention delegates were still selected at caucuses run by state party insiders. The national conventions remained the high stakes, high drama events at which presidential nominations were actually decided.

By 1968, however, American politics were changing again. The nation was marked by episodes of civil unrest that followed the assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr. in April and Senator Robert F. Kennedy in June. The stage was set for a contentious Democratic National Convention, to be held in August in Chicago. More than any other issue, the raging war in Vietnam divided both the nation and the Democratic Party. The two anti-war candidates, Senator Kennedy and Senator Eugene McCarthy, had won the overwhelming support of voters in the fourteen states that held primaries. After a disappointing New Hampshire primary result, President Lyndon Johnson withdrew his candidacy for re-election. Vice President Hubert Humphrey, inextricably tied to America's involvement in the war, competed only in party-run caucuses.

The Chicago Convention will forever be remembered for its devolvement into chaos. Ten thousand protesters amassed in the city to impress their anti-war views upon attending delegates. Many became entangled in violence with thousands of law enforcement and military personnel. A furious mayhem, both outside and inside the convention hall, was televised to a national audience. In the end, Vice President Hubert Humphrey won the Democratic nomination, a result that underscored the wide gulf between party leaders and public opinion.

The turmoil of the 1968 Democratic National Convention brought about significant reforms to the nomination process. By the following election cycle, both major parties instituted rules that opened primaries and caucuses to more meaningful voter participation. Most states now hold presidential primary elections that lead to the selection of pledged delegates, proportionally favoring the primary winner. States and parties differ in their rules for allocating delegates, but today's primaries and caucuses gauge popular support for presidential candidates, and the results almost always determine the nominees. As a result, the main purposes of today's national party conventions are to celebrate the voters' choice of nominee and his or her choice of running mate, and to formally launch the general election campaign.

Republican Nominating Convention, Chicago 1888 (Benjamin Harrison)

1912 William Taft campaign button, lost election to Woodrow Wilson

Press Pass to the legendary 1968 Chicago Democratic Convention

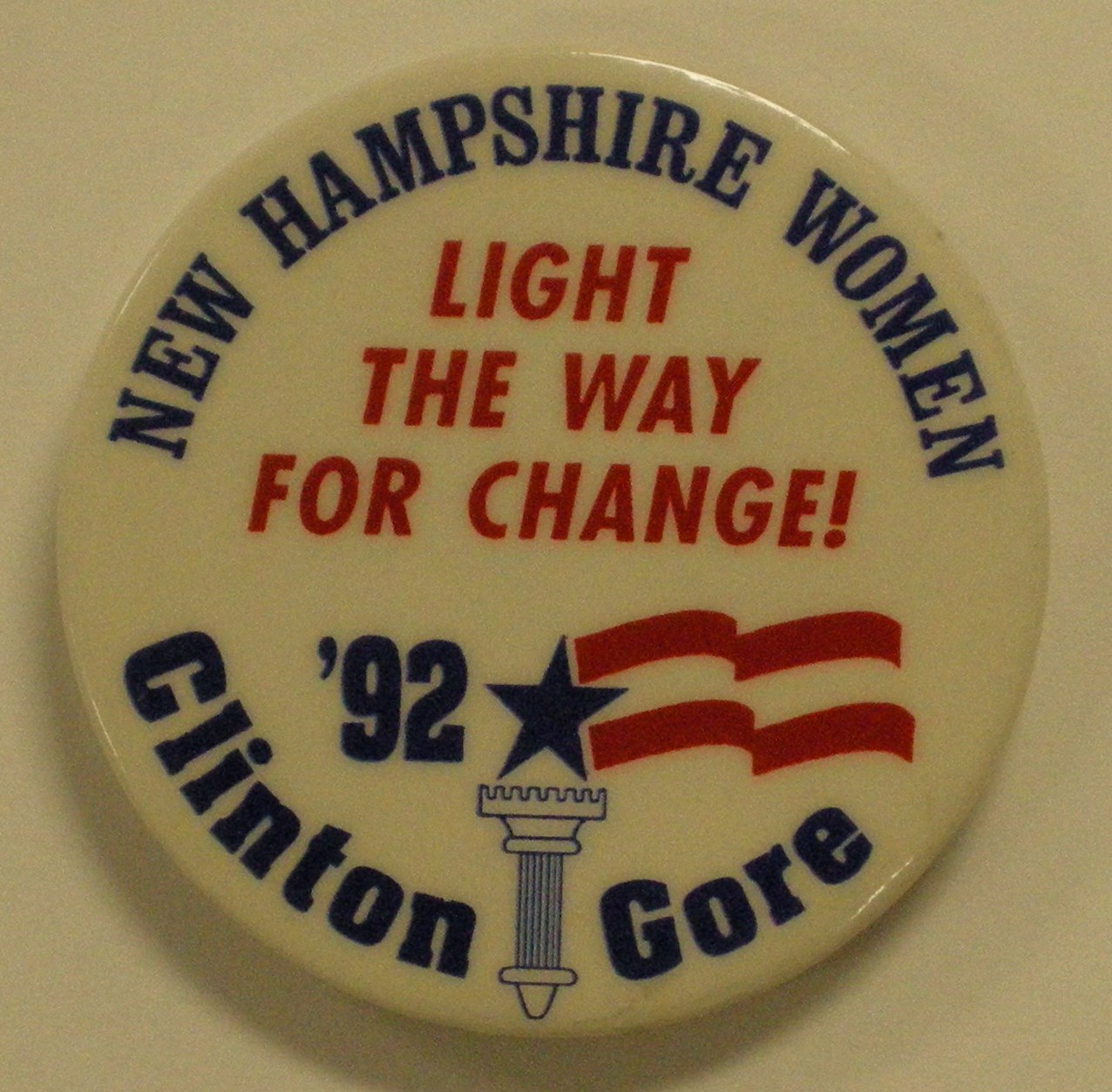

Campaign button for Bill Clinton who won the election

beating President George H. W. Bush

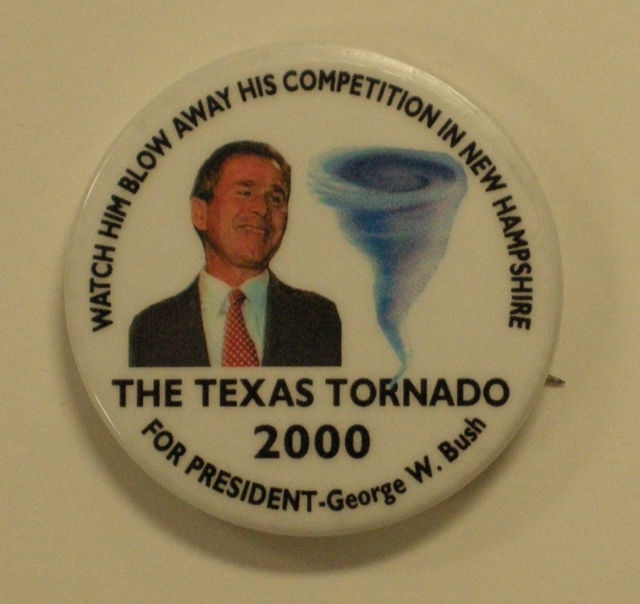

George W. Bush’s campaign button, won the highly

controversial election over Al Gore

1980 Detroit Republican Convention