21. Learning the Law in New Hampshire

Located: 1st floor conference room inside Courtroom B vestibule

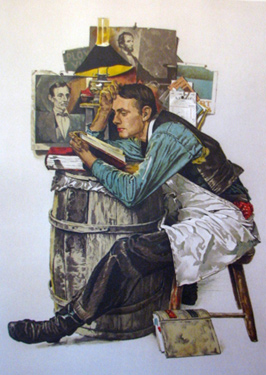

Print in courthouse exhibit: Norman Rockwell, The Law Student (Saturday Evening Post Cover, February 19, 1927)

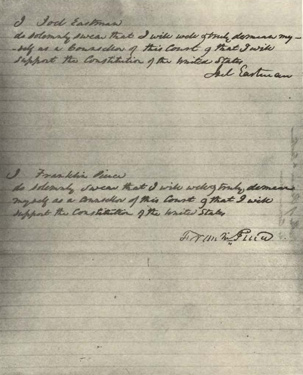

Other images of interest: NH Bar Association photo of new lawyers, 1965; Franklin Pierce oath as a new lawyer in the District Court

New Hampshire’s colonial Court of General Sessions of the Peace first admitted lawyers to practice in 1686. While bar chapters existed in at least some counties over the following one hundred years, the first recorded statewide meeting of lawyers occurred in 1788. The New Hampshire Bar Association was incorporated by a special act of the legislature in 1873, making it the oldest statewide bar organization in the nation.

From the days of reading a borrowed copy of Blackstone's Commentaries on the Laws of England to the current requirements for a legal education, this essay considers the history of paths to practicing law in New Hampshire. This essay provides a short history of the paths to practicing law in New Hampshire.

Learning the Law

In 1686, Henry Dow of Hampton and John Pickering of Portsmouth became the first lawyers admitted to the “general bar” of New Hampshire. Neither man had any formal education, which suited New Hampshire settlers just fine. Early colonial America had little use for lawyers. Disputes were commonly resolved pursuant to rules of fairness, good sense, and Puritan ethics. Englishmen who had trained in London’s Inns of Court were often assumed to be tied to British commercial interests, and therefore viewed with suspicion. If there had to be any “lawyers,” honest but untrained men would do.

By the early 1700s, however, America’s growth placed new demands on colonial life. Business ventures and land transactions required properly drafted contracts with enforceable terms. Representative assemblies, courts, and governmental officials needed legal opinions. Lawyers were a necessity in America after all; and colonists decided to learn the profession. Some men (mostly from southern colonies, and only those who could afford the substantial time and expense) traveled to London for up to three years of traditional barrister training. Others apprenticed in the offices of colonial lawyers already in practice, or worked as court scribes or government assistants, picking up whatever knowledge in the law they could. Many others decided to “read the law” on their own.

None of these options was a sure foundation for a successful legal career. Those who ventured to London found that the Inns of Court had essentially become social clubs during this period, no longer offering the moot courts or structured readings that had defined their long-standing reputation of excellence. In the American colonies, the quality of law apprenticeships and clerkships varied greatly. While some lawyers provided clerks with a productive program of reading, observation and discussion, apprenticeships often consisted of mindlessly copying legal documents, and doing the menial chores required to keep an office clean and warm. Those who tried to “read the law” in self-study had a hard time finding law books to borrow and a harder time deciphering their difficult presentations of cases and commentary.

Mastery of the common law was supposed to come from digesting reports of medieval and Tudor cases, codified and commented on by Sir Edward Coke in 1628, along with other dated legal treatises. Reading Coke’s works was a grueling, tedious endeavor that was known to discourage most would-be lawyers. Still, determined aspirants stuck with the path they chose until they were able to persuade the established bar to admit them, and bar memberships grew. By the mid-1700s, a mixture of trained and semi-trained lawyers, most having at least some knowledge of English common law, shared the legal workload of bustling communities throughout the colonies.

Sir William Blackstone’s straight-forward and understandable lectures on the laws of England, delivered at Oxford University between 1753 and 1763, introduced a seismic change in learning the law. With the publication of Blackstone’s Commentaries in 1765, and the American edition in 1771, lay readers on both sides of the Atlantic found they were finally able to make sense of England’s common law rules and precedents, including real property, torts, and criminal law. From the time of the American Revolution until the twentieth century, no other resource for legal education was used more regularly, or relied on more heavily, than Blackstone’s Commentaries.

The political evolution leading towards an independent United States propelled a surge in interest in the law. A decade before the new nation was formed, New Hampshire’s bar was still very small, with just eight attorneys practicing in the colony. (One well-known New Hampshire lawyer was John Sullivan, who in 1789 would become this court’s first district judge). Soon after the Revolution, most states introduced new requirements for professional practice. In 1788, the state of New Hampshire set comparatively strict rules for bar admission, including a college degree and three years of law study (or, in the absence of a degree, five years of study).

By 1800, there were 80 admitted members of the bar in New Hampshire. In 1804, two new requirements for bar membership were added: good moral character, and “suitable proficiency in the knowledge of the law,” as determined by examination, to be administered by the relevant county bar association. By 1830, the number of lawyers in New Hampshire had jumped to 232, most of whom were college graduates, and all of whom had completed years of legal study or apprenticeship. With the advent of “Jacksonian democracy” in 1832, however, educational qualifications for the practice of law were widely viewed as unfair and elitist, and were abandoned across the nation. By 1842, permission to practice law in the state of New Hampshire was granted to any petitioner of “good moral character” who was at least 21 years old. Only after the end of the Civil War did states begin to reinstate professional qualifications for lawyers. New Hampshire’s legislature created the first state-wide bar association in 1873; and in 1886, New Hampshire became the first state to appoint a single committee of the bar, the Board of Bar Examiners, to examine all candidates for admission to practice.

The Tapping Reeve Law School in Litchfield, Connecticut, blazed an early trail for classroom learning of the law between 1744 and 1833, with about 1,100 young men from all parts of the United States attending. Levi Woodbury of Francestown, New Hampshire, studied there in 1809, making him the first United States Supreme Court Justice to attend law school. Well into the late 1800s, the most popular methods for learning the law continued to be apprenticeship and self-study, even as a growing number of universities offered a law school curriculum. The case method of study, first introduced in about 1870 at Harvard, represented a radical change in teaching law. This new, American approach shifted the emphasis away from memorizing legal rules in the abstract, and toward analyzing the application of legal principles and precedent to a case at hand. The case method of study is still employed in law schools across the country, although not as an exclusive method.

Educational requirements for New Hampshire bar admission were significantly tightened in the twentieth century. From the late 1800s until 1948, applicants had to have the equivalent of a high school education, plus three years of law study prior to taking the bar exam. As law schools became more prevalent across the country, the process of “reading law” became less accepted. By 1960, New Hampshire required that its candidates for bar admission have completed college and law school prior to examination. Only six states in the nation currently allow a legal apprenticeship as preparation for the bar exam and the practice of law. While debate continues over the best way to prepare law students for professional practice, most American law schools blend lectures, discussions, examinations, and practical experience into a three-year curriculum of study.

The first and only law school located in New Hampshire, the Franklin Pierce Law Center, was founded in 1973. Today, the law school is a part of the University of New Hampshire system.