16. The Civilian Conservation Corps

Located:1st floor, alcove outside Courtroom B

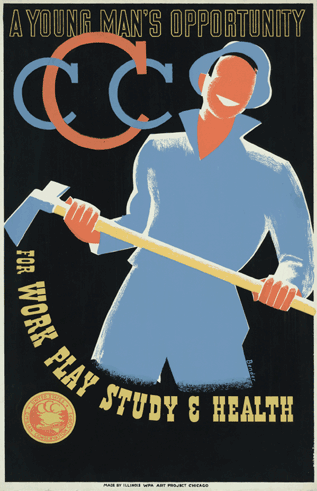

Prints in courthouse exhibit: CCC First Corp Area Honor Company. This photo of Company 155 Civilian Conservation Corps was taken in Gotham NH in October 1940, Poster promoting the U.S. Civilian Conservation Corps in the state of Illinois. Created by the Illinois WPA Art Project in 1941.

When Franklin Delano Roosevelt assumed the Presidency in March, 1933, the nation had already endured nearly four years of financial strain. A week before his inauguration the failure of thousands of banks had finally caused a panic, prompting a government-ordered “bank holiday” in all 48 states. At least twenty-five percent of the American workforce was unemployed. Traditionally stable wage earners found themselves jobless and their homes in foreclosure. Widespread fear of the worsening situation gripped struggling households in every region of the country.

FDR’s Civilian Conservation Corps: A Part of New Hampshire’s Landscape

When Franklin Delano Roosevelt assumed the Presidency in March, 1933, the nation had already endured nearly four years of financial strain. A week before his inauguration the failure of thousands of banks had finally caused a panic, prompting a government-ordered “bank holiday” in all 48 states. At least twenty-five percent of the American workforce was unemployed. Traditionally stable wage earners found themselves jobless and their homes in foreclosure. Widespread fear of the worsening situation gripped struggling households in every region of the country.

“This is a day of national consecration,” the new president boldly proclaimed in his inaugural speech. “This great Nation will endure as it has endured, will revive and will prosper. So, first of all, let me assert my firm belief that the only thing we have to fear is fear itself – nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror which paralyzes needed efforts to convert retreat into advance….”

The President outlined immediate “lines of attack” to improve the economy, including efforts to assist farmers, prevent foreclosures, and regulate banking. He prioritized the plight of the unemployed in bold and focused terms: “Our greatest primary task is to put people to work,” said the President, “… by treating the task as we would treat the emergency of a war, … [and] accomplishing greatly needed projects to stimulate and reorganize the use of our natural resources.”

Roosevelt’s steady message urged a renewed national optimism, and quick action followed. Within days of the inauguration, Congress passed legislation permitting the reopening of banks that could prove their solvency. As for the unemployment emergency, new public relief initiatives were high on President Roosevelt’s agenda, “not as a matter of charity but as a matter of social duty.” Fundamentally, Roosevelt believed that productive work projects should be the primary form of government assistance.

The Civilian Conservation Corps

The President himself conceived of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), the first of several work-relief programs of the New Deal. The CCC aimed to employ young men in the reclamation and preservation of America’s neglected public lands and natural resources. The national forestry work that Roosevelt envisioned was necessary, he said, to save America from becoming “a very large lumber-importing nation” by mid-century. The President was also convinced that downtrodden, jobless young men would benefit both physically and mentally by meaningful outdoor work. “We are clearly enhancing the value of our natural resources, and second, we are relieving an appreciable amount of actual distress,” he explained in an early “Fireside Chat” radio address.

The speed by which “Roosevelt’s Tree Army” was organized and mobilized astonished even the harshest critics of the plan. The only serious debate over the program concerned the proposed pay to enrollees: $30 per month, with $25 of it sent directly to each worker’s family. Although the dollar-a-day formula was controversial (some argued that it would lower the standard wage in the working world), Congress quickly approved the program. By early July, the CCC employed, fed, clothed and boarded 250,000 unmarried men between 18 and 25 years of age in 1,463 camps near project sites. With U.S. Army Reserve Officers in charge, CCC camps were soon operating in all 48 states. Between 1933 and 1942, nearly 3 million men signed up for at least one six-month term in the CCC.

Roosevelt’s “New Deal” instituted several, much larger public work initiatives, including the Civil Works Administration (CWA), the Public Works Administration (PWA), and the Works Progress Administration (WPA). Between 1935 and 1941 the WPA put over 3 million people to work annually (ten times more than the CCC), modernizing the country’s infrastructure and providing a wide range of public services. For many, however, it was the CCC’s call for America’s idle youth to work in the rugged outdoors, sustaining their destitute families while improving the condition of the nation’s natural resources, that conjured a powerfully optimistic image of America’s future. The CCC’s mission, enthusiastically heralded by the President, ensured its popularity.

New Hampshire and the CCC

Life in New Hampshire’s 28 Civilian Conservation Corps camps, like those around the nation, followed a basic military-style outline. A bugler’s early morning reveille signaled the start to each day, followed by a structured schedule of work under the supervision of the U.S. Forestry Service. Young men from rural New Hampshire lived and labored with those who had come north from New England’s larger cities, often never having spent time in the woods.

Three square meals a day, the camaraderie of peers, a warm place to sleep at night … these were luxuries for many “CCC boys”. The Corps provided a break from the brutal reality of the Depression, and made use of their youthful vigor. Daily physical labor and a diet of healthy food combined to add an average of 11 pounds to each enrollee.

Today’s visitors to New Hampshire’s White Mountain National Forest and numerous state parks are still surrounded by the legacy of the CCC. Camp enrollees built bridges, culverts, and dams to address and prevent flood damage, added firebreaks to the forests, thinned out harmful undergrowth, and planted trees. They cut ski trails and hiking trails reaching remote recreational vistas. They laid new roadways and widened existing ones, and installed telephone lines. Fish hatcheries, campgrounds, recreation fields and facilities, public beaches – the projects were numerous, and many remain in service today. Nine years of work by a total of 36,694 New Hampshire CCC camp enrollees dramatically reinvented the public’s relationship with, and access to, the great outdoors.

Besides regularly assigned projects, New Hampshire’s CCC camps were frequently called upon to assist in emergencies, including fighting forest fires. Floods in 1936 and the great hurricane of 1938 further tasked the CCC boys with essential life and property saving work.

Throughout the popular program’s tenure, rumors of its discontinuance were met with public outcries. After nearly a decade, however, the unemployment rate dropped precipitously as the threat of war compelled substantial expenditures on national defense. In 1942, the Civilian Conservation Corps was finally disbanded.

Poetry of the New Hampshire CCC

Builder of Men

Before we thought of coming in,

We were considered pale and thin

My friend and I oft used to roam,

And rarely were we seen at home.

Thus leaving at home a group of eight,

We joined this camp to put on weight.

The first night we were very ill,

And pretty near went o’er the hill,

But in body and mind we sure did grow.

Now we’re not pale, forlorn or weak,

There’s a glow of color in our cheek.

No longer ashen, thin or frail,

We’re both as hard as any nail.

So we proudly stand, salute and then,

Cheer aloud for the builder of men.

- by Paul Snow and Alcide Tremblay, of CCC Camp Warner

- Builder of Men by David D. Draves (foreword)

Dividends

A “buck” a day is all we’re paid

But yet this morning in a glade

I saw a deer, a pretty thing.

Until I started working here

Just think, I’d never seen a deer.

(Of course I may have seen a few

Moping and hoping in a zoo)

Another thing I never knew

Is what the smell of pines can do

In somehow helping you to find

the real resources of your mind.

I feel – it may sound odd –

We’re getting extra pay from God.

- by a young man enrolled in a New Hampshire CCC camp during the 1930’s-

- printed in The New Hampshire Troubadour, 1948.

- Builder of Men by David D. Draves, p. 343