15. Made in New Hampshire: International Pledges for Peace and Security

Located: 1st floor, alcove outside Courtroom B

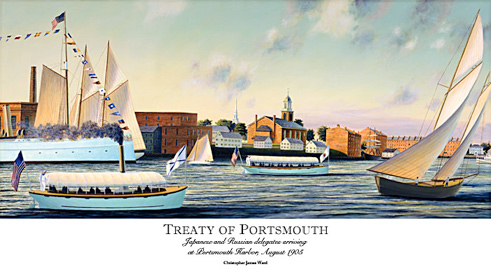

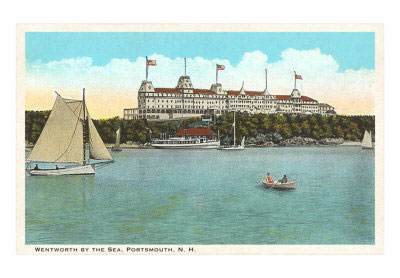

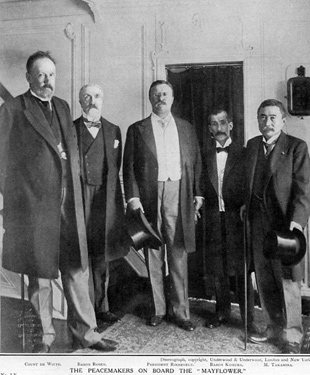

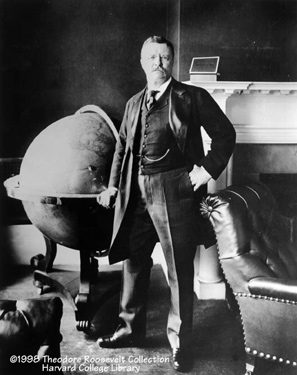

Prints in courthouse exhibit: Christopher Ward, Treaty of Portsmouth, Japanese and Russian delegates arriving at Portsmouth Harbor, August, 1905; early twentieth-century postcards of the Wentworth Hotel and Bretton Woods; photo of Theodore Roosevelt with globe; photo of Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Winston Churchill.

Other image of interest: Photo of T. Roosevelt with Russian and Japanese diplomats.

Two significant international conferences were held on New Hampshire soil during the twentieth century. The Portsmouth Peace Conference, called by President Theodore Roosevelt in 1905, hosted negotiations between the Japanese and Russian governments to end hostilities which threatened world peace, over land bordering the Yellow Sea. The peace agreement between the two nations firmly established America’s leadership role in world affairs, and earned Roosevelt the 1906 Nobel Peace Prize.

The “Bretton Woods Conference” (United Nations Monetary and Financial Conference), held in July, 1944, just weeks after the allies’ invasion of Normandy, hosted representatives of forty-four nations. The object, to create “an enduring program of future economic cooperation and peaceful progress,” required the tireless work of famed economists John Maynard Keynes of Great Britain and Henry Dexter White of the United States, as well as the diplomatic involvement of the world’s developed and growing economies. The conferees arrived at a system to govern global monetary policy and established both the International Monetary Fund and the predecessor organization to the World Bank, two institutions that continue in operation today.

Made in New Hampshire:

International Pledges for Peace and Security

When Theodore Roosevelt became President in 1901, the nation had already experienced war for its own sovereignty and territory in five distinct conflicts. In 1905, when he took the lead in facilitating an end to the Russo-Japanese War, America was fast becoming a key player in determining external world affairs as well.

By 1944 America was the strongest military and economic force in the world and, even in the midst of yet another war, wielded great diplomatic power and influence. Emulating his distant cousin “Teddy,” President Franklin Delano Roosevelt assumed the responsibility for an orderly transition from war to peace. A full year before the end of World War II, he invited countries from around the globe to convene on the essential question of global economic security.

In both instances, the Roosevelt presidents desired tranquil and private accommodations for conducting negotiations toward world peace and prosperity. They looked to the Granite State, known for its scenic beauty, mild summers and grand hotels, as the perfect host location.

The Treaty of Portsmouth, 1905

On February 8, 1904, Japan launched a surprise attack against the Russian Navy’s occupation of Port Arthur, an ice-free Chinese port on the Yellow Sea. Japan had proved its military might against China in 1895 and would not tolerate Russian Czar Nicholas’ growing interest in the Far East. By the summer of 1905, the furious conflict over territorial rights to southern Manchuria, Korea and Sakhalin Island had claimed 150,000 lives.

As the Russo-Japanese War escalated, so did the level of global concern about its outcome. At this time of colonial and trade competition, France, Great Britain, Germany and Spain were intently focused on the sparring. President Theodore Roosevelt wanted to secure a negotiated peace before these or other nations joined the conflict. He managed to convince the incensed Russian and Japanese leaders to hold settlement talks on the comparatively neutral grounds of the United States.

President Roosevelt, the former Assistant Secretary of the Navy, chose the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard as a secure and fitting location for the peace conference. The small city of Portsmouth offered a quiet charm within an easy sail of the President’s summer home in Oyster Bay on Long Island. Wentworth-by-the-Sea, a grand hotel on the island of New Castle with coastal and mountain views, provided proper, stylish and relaxing accommodations for the late-summer visit by foreign dignitaries. The President also counted on the region’s typically cool summer weather, likely the American assembly’s only serious disappointment during New Hampshire’s sweltering heat of August 1905.

Barely a month before the foes’ scheduled meeting in Portsmouth, Japan triumphantly overran Sakhalin Island, as if to add an exclamation point to its repeated battle victories. But the Japanese Empire’s impressive military prowess was ultimately upstaged by Roosevelt’s success in bringing these warring enemies to the calming waters of the New England coast to hammer out a settlement of their grievances. The Peace Conference put the American President’s intellect and diplomatic skills fully on display before a world audience.

Perhaps the greatest asset Portsmouth offered was its people, virtually none of whom ever expected to figure significantly in fostering peace between foreign nations. Portsmouth city officials and residents joined New Hampshire Governor John McLane in extending gracious and generous hospitality to the diplomatic teams. Historians even credit Portsmouth natives as diplomats in their own right; through their informal encouragement of the mission of peace, they became essential participants in what is now known as “multi-track diplomacy.”

President Roosevelt approached the talks with America’s interest in the balance of international power foremost in his mind. His desire to stymie the overly eager Russian czar’s advances was tempered with a realist’s understanding that tiny but militaristic Japan could create havoc for western trade and political interests. As agreed by the parties, Roosevelt stayed away from Portsmouth, but he took an active role when necessary. Brokering the negotiations was not easy. After a month of work, the conference nearly collapsed due to the parties’ recalcitrance. Called by writer Henry Adams “the best herder of Emperors since Napoleon,” Roosevelt doggedly pressed both sides to agree on terms to end the conflict. His persistence paid off. The Treaty of Portsmouth was finally signed on September 5, 1905.

Although World War I would erupt only nine years later, Russia and Japan remained at peace for four decades following the treaty. Significantly, the peace achieved at Portsmouth firmly established America’s leadership in world affairs. This reality greatly influenced the following forty years of global strife and conflict, and continues to define our nation’s foreign diplomacy.

Theodore Roosevelt enjoyed considerable recognition for mediating the Treaty of Portsmouth. He was awarded the 1906 Nobel Peace Prize, the first American Nobel laureate in any category.

The “Bretton Woods Conference” (United Nations Monetary and Financial Conference), 1944

As the allied forces contemplated victory in both the European and Pacific theaters of World War II, plans were laid for a post-war and post-Great Depression world. The economic situation was grave; virtually every country but the United States would leave the war saddled with huge debt. President Franklin Roosevelt believed that international free trade would promote worldwide prosperity and peace, and strongly advocated the formulation of a monetary system to support this ideal. As early as August 1941, meeting at sea for their “Atlantic Conference,” President Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill agreed their nations would endeavor “to further the enjoyment by all States, of access, on equal terms, to the trade and to the raw materials of the world which are needed for their economic prosperity.” The “permanent system of security” they envisioned would require global economic cooperation.

American Treasury expert Henry Dexter White and renowned British economist John Maynard Keynes each crafted a means to this end. Among their shared ideas were to establish orderly exchange rates and to provide financial assistance to countries facing balance of payments deficits, thus discouraging trade protectionism and promoting economic expansion. White and Keynes held numerous discussions to formulate a workable approach to these concepts, and consulted in 1943 with technical experts from twelve other countries. President Roosevelt then invited delegations from around the world to “this quiet meeting place,” the Mt. Washington Hotel in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, to confer on the establishment of a new international monetary system.

A journey across the oceans in June of 1944, the month of the Invasion of Normandy, was dangerous and complicated. Nevertheless, forty-four countries sent representatives to participate at Bretton Woods. While the scenic and peaceful White Mountains offered a respite from many attendees’ hardships of war, the grand hotel was filled beyond capacity with 730 finance ministers, delegates and clerks needing accommodations. At least New Hampshire offered relatively cool summer weather; Keynes had pleaded with White not to “take us to Washington in July, which should surely be a most unfriendly act”.

In his welcoming address to the Conference, Franklin Roosevelt noted with characteristic optimism, “It is fitting that even while the war for liberation is at its peak, the representatives of free men should gather to take counsel with one another respecting the shape of the future which we are to win.” But creating “an enduring program of future economic cooperation and peaceful progress” required intense and difficult work. Daily committee meetings extended into late nights of budgeting, forecasting and negotiating. The multitude of spoken languages made communicating the methods and conclusions of Keynes, White and other experts an all-consuming task. Local Boy Scouts scurried back and forth as microphone handlers, allowing speaker after speaker to contribute to the discussions.

After three full weeks, with input and agreement secured from all corners of the world, the participants settled on a new system to govern monetary policy among nations. All parties to the Bretton Woods Agreement would peg their currencies to gold, with the U.S. dollar deemed convertible to gold at a specific value. This fixed exchange rate system worked to stabilize the world economies until 1971, when pressure on the United States economy led to its replacement by a floating exchange rate system. Two permanent organizations to support the fragile monetary relationship between nations were also established: the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, the latter of which is today a part of the World Bank Group. These “Bretton Woods Institutions” still serve their original purposes: to promote foreign trade and assist countries with short-term exchange difficulties; and to provide longer-term loans to nations in need of reconstruction and development. They have evolved with the increasing demands of a changing world, earning both the support and criticism of governments and scholars.

Franklin Roosevelt and Winston Churchill’s vision for global economic cooperation, set in motion by the Bretton Woods Conference, was no small achievement. The accord reached on these large and complex matters were without precedent in the history of international economic relations. In the midst of world war, the conference marked a unified intention to safeguard future world security.

Treaty of Portsmouth - (Christopher J. Ward)

Early Twentieth Century Postcard of Wentworth By the Sea

President T. Roosevelt with Russian and Japanese diplomats (1905)

Portrait of Theodore Roosevelt - Harvard College Library

Early Twentieth Century Postcard of Bretton Woods, The Mount Washington

FDR and Churchill