46. The Third Branch: Principles of American Jurisprudence

Located: 3rd floor, east alcove extension outside Courtrooms 4 and 5

Photo in courthouse exhibit: U.S. Supreme Court Building, West Pediment - Franz Jantzen, Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States

Other images of interest: Checks and Balances diagram, St. John Fisher College; Thomas Jefferson quote on juries; Norman Rockwell, Jury Holdout (1959)

Three essays are arranged to resemble pillars upholding the West Pediment of the U.S. Supreme Court Building in Washington, D.C., and its famous inscription, “Equal Justice for All”. The first text, “Three Branches, Two Balancing Acts,” considers the constitutional framework of America’s federal judicial system, and its interplay with the legislative and executive branches of the government. “Trial by Jury – The Anchor of Justice” presents a brief history of jury trials and their significance to maintaining an independent judiciary. The third essay, “The Presumption of Innocence – The Golden Thread,” takes a look at our criminal legal system’s most famous doctrine: that which places the burden of proof firmly with the prosecution, thereby protecting innocent persons from potential abuses of unconstrained state power.

Essays

Three Branches – Two Balancing Acts

When the framers of the United States Constitution shaped the structure of the federal government, they struggled with two of three major issues confronting a more permanent unification of the thirteen loosely associated colonies. Dissatisfaction with the Articles of Confederation, which had established a weak central government, ultimately led to the drafting of a new constitution in 1787. With this new constitution, the framers strove to create a document that would balance power between the federal government and the states and also balance power within the federal government itself. The third major issue, slavery, was left for another day.

This new constitution established a bicameral legislature with fairly apportioned representation for both large and small states and gave the federal government the power to collect taxes, declare war, command a military and regulate commerce among the states. Alexander Hamilton, James Madison and John Jay anonymously published a series of essays, now known as The Federalist Papers, in support of the new constitution. In Federalist No. 46, Madison attempted to quell fears of a strong centralized federal government by reminding citizens that “ambitious encroachments of the federal government, on the authority of the State governments, would not excite the opposition of a single State, or of a few states only. … Every government would espouse the common cause.” (emphasis added)

Madison also noted that because citizens will likely remain attached to the governments of their respective states, partiality toward the federal government would only result from “manifest and irresistible proofs of a better administration.” By 1789, Madison would propose a Bill of Rights, including the Tenth Amendment’s guarantee that “[t]he powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.”

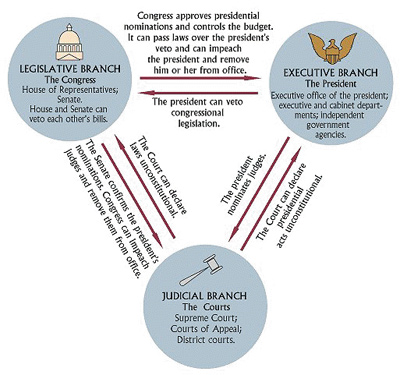

In addition to balancing power between the states and the federal government, the framers looked to the British parliamentary system as a model and established three branches of government with a system of checks and balances on the power of each branch. This political structure, based on the doctrine of separation of powers, was first developed in ancient Greece and then adopted by the Roman Republic. Later, during the Age of Enlightenment in Europe, philosophers John Locke and Baron de Montesquieu (generally credited with coining the phrase “separation of powers”) advocated for separate branches of government to prevent abuse of power.

Article I of the Constitution establishes the legislative branch, which consists of the House of Representatives and the Senate, and grants it the sole power to make laws via legislation. Article II establishes the executive branch, vesting in the president the power to carry out the laws of the United States and to act as the civilian commander in chief of the military. As a check on the power of the legislature, the president has the power of veto. The legislature, in turn, may override a veto in most cases with a two-thirds majority vote. As commander in chief, the president may take military action in the event of a crisis, but only the legislative branch has the power to declare war.

Article III of the Constitution establishes the judicial branch, specifically the United States Supreme Court, reserving for Congress the authority to establish “lesser courts.” With the Judiciary Act of 1789, Congress organized a system of district and circuit courts. Article III grants the judiciary the power to decide cases and controversies. The power of judicial review provides a vital check on the power of the legislative and executive branches. For example, the federal judiciary has the power to strike down a law enacted by Congress if it is unconstitutional.

The Constitution does not explicitly discuss this power of judicial review; however, the Federalist Papers indicate the concept was strongly supported by the framers. In Federalist No. 78, Hamilton expressed his belief that federal courts have a duty to interpret and apply the Constitution. He stated, “[T]he courts were designed to be an intermediate body between the people and the legislature, in order, among other things, to keep the latter within the limits assigned to their authority.” The U.S. Supreme Court did not exercise its power to strike down an act of Congress until 1803 in Marbury v. Madison. Regarding the Court’s decision, Chief Justice John Marshall stated, “It is emphatically the province and duty of the Judicial Department [the judicial branch] to say what the law is. Those who apply the rule to particular cases must, of necessity, expound and interpret that rule. If two laws conflict with each other, the Courts must decide on the operation of each.”

In addition to the power of judicial review, the judiciary’s independence helps ensure a balance of power in the federal government. In Federalist No. 78, Hamilton remarked, “[T]he independence of the judges may be an essential safeguard against the effects of occasional ill humors in the society.” Rather than being subject to elections, federal judges are appointed to lifetime terms and vacate office only upon death, resignation or impeachment by Congress. The judiciary’s relative freedom from political influence, and from interference by the other branches, allows judges to make decisions according to the rule of law rather than public opinion or political pressures.

The rule of law, or the notion that governmental decisions stem from the application of recognized legal principles, fosters consistency, restricts discretionary power, and ensures that all persons are subject to the law, including those in power. Legal scholars and activists, including the International Bar Association and the World Justice Project, have stated the rule of law protects fundamental human rights and is a key element of a humane and just society. In a 2005 resolution, the International Bar Association stated, “The rule of law is the foundation of a civilized society. It establishes a transparent process accessible and equal to all. It ensures adherence to principles that both liberate and protect.”

Daniel Webster noted in 1845 that justice is “the great interest of man on earth” and “the ligament which holds civilized beings and civilized nations together.” The federal judiciary, also known as the government’s “third branch,” plays an essential role in a political system designed to balance power, provide justice and hold our civilized nation together. Established over two centuries ago, the three branches of the American federal government serve as a standard for democratic governments worldwide and demonstrate the enduring impact of the framers’ two balancing acts.

The Presumption of Innocence - The Golden Thread

The presumption of innocence, or the principle that one accused of a crime is considered innocent until and unless proven guilty, is a fundamental legal right in the United States and many other nations. The presumption places the burden of proof in a criminal trial on the prosecution, rather than on the defendant. In the United States, the prosecution is charged with proving guilt beyond a reasonable doubt, whereas a defendant has no obligation to prove his innocence and does not have to testify, call witnesses or present any other evidence. A defendant’s decision not to testify or present evidence cannot be held against him or interpreted as any sort of admission of guilt. John Sankey, Lord Chancellor of Great Britain from 1929 to 1935, referred to the burden on the prosecution as the “golden thread” in the web of English criminal law.

The presumption of innocence can be traced back to the Babylonian Code of Hammurabi and the laws of Ancient Sparta and Athens. The Digest of Justinian from the sixth century includes the following statement: “[P]roof lies on him who asserts, not on him who denies.” The Magna Carta arguably codified the presumption of innocence in 1215, as it guaranteed royal subjects impunity from imprisonment, or other punishment, except through due process of law. Thirteenth century French cardinal and jurist Jean Lemoine also advocated for the presumption of innocence, based on the inference that most people are not criminals.

Following its inclusion in the Magna Carta, the presumption of innocence was gradually incorporated into European common law and, later, into the common law of the American colonies. English lawyer Sir William Garrow (1760-1840) is often credited with coining the phrase “innocent until proven guilty,” and insisted that the accuser, not the accused, be tested in court. In 1760, William Blackstone declared in his Commentaries on the Laws of England, “[B]etter that ten guilty persons escape than that one innocent suffer.” Though Blackstone was not the first to express this principle, it became commonly known as Blackstone’s formulation and was later echoed by many legal thinkers, including John Adams and Benjamin Franklin. John Adams viewed the presumption of innocence as essential for maintaining order and civility. He wrote:

It is more important that innocence be protected than it is that guilt be punished, for guilt and crimes are so frequent in this world that they cannot all be punished. But if innocence itself is brought to the bar and condemned, perhaps to die, then the citizen will say, “whether I do good or whether I do evil is immaterial, for innocence itself is no protection,” ….

Though it was never formally incorporated into the United States Constitution, American jurists acknowledge that the presumption of innocence “is a basic component of a fair trial under our system of criminal justice.” Estelle v. Williams (1976). . In Coffin v. United States (1895), a landmark case on the presumption of innocence, the Supreme Court traced the history of the principle and established it firmly as a fixture of American common law. The Coffin Court held that, at the request of the defendant, a court must instruct the jury on the defendant’s presumed innocence. The Court noted, “The principle that there is a presumption of innocence in favor of the accused is the undoubted law, axiomatic and elementary, and its enforcement lies at the foundation of the administration of our criminal law.”

In support of its decision, the Coffin Court declared that “this presumption is to be found in every code of law which has reason and religion and humanity for a foundation.” Presently, the presumption of innocence is found in many legal codes and constitutions, and many nations and humanitarian organizations consider it a fundamental right. Article 11 of the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights specifically states, “Everyone charged with a penal offense has the right to be presumed innocent until proved guilty according to law in a public trial at which he has had all the guarantees necessary for his defense.”

The presumption of innocence remains a nearly universal principle embedded in democracies and republics throughout the world, including the United States. It has been called both a bedrock rule and a golden thread running through the criminal justice system. When woven into a constitution or the common law, this golden thread steadfastly preserves defendants’ rights and protects innocent persons accused of crimes.

Trial by Jury – The Anchor of Justice

Though it has ancient origins, the trial by jury has evolved into an essential element of the modern legal system. In many federal criminal cases, the trial by jury protects the rights of the defendant, as the government cannot infringe upon the defendant’s freedom until and unless twelve citizens are convinced of the defendant’s guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. During the American Revolution, many American colonists considered trial by jury an indispensable right. When drafting the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson included deprivation of that right in the list of grievances against the British king. Regarding the importance of jury trials, Thomas Jefferson considered them “the only anchor yet devised by man, by which a government can be held to the principles of its constitution.”

The concept of a legal proceeding in which a jury of citizens makes findings of fact first developed in Ancient Greece and Rome. In Greece, a jury typically consisted of hundreds (and sometimes over a thousand) citizens if the case involved death, loss of liberty, exile or seizure of property. Rather than requiring a unanimous verdict, these ancient juries employed majority rule. Rome employed tribunals with the characteristics of a jury, as the judges were lay people not trained in law, who were selected on a yearly basis.

Juries were utilized to a lesser extent during the Middle Ages in England. Jurors were required to investigate a case themselves before reaching a decision, rather than obtaining information through a trial. Henry II, who ruled England from 1154 to 1189, set up a system to resolve land disputes involving panels of twelve “free and lawful men.” He also established a presenting jury responsible for reporting crimes, which could be viewed as a precursor to the modern grand jury. Criminals accused by the presenting jury, however, were then subjected to a trial by ordeal.

A trial by ordeal, a historical method of administering “justice” that would now be considered barbaric, stands in stark contrast to a trial by jury. These typically subjected the accused to a painful or harmful experience. Survival of the experience and healing of injuries was viewed as a result of divine intervention and, thus, determined guilt or innocence. An ordeal of fire typically required the accused individual to walk across a length of red-hot metal or to retrieve a stone from a vat of boiling water or oil.

Trials by ordeal fell out of favor in the early thirteenth century and the Magna Carta (1215) established the trial by jury as a right in England. The Medieval juries were initially self-informing, but over time grew to rely more on evidence presented at trials for information, rather than on independent investigation. Many British colonies, including those that became the United States, adopted the practice of jury trials. Prior to and during the Revolutionary War, however, the British Parliament passed several measures limiting the right to trial by jury for colonial Americans. When colonial juries refused to convict defendants charged under the unpopular British Navigation Acts, the British government moved the cases to admiralty courts that did not use juries.

After the colonists won independence from Britain, the United States Constitution formally preserved the right to trial by jury. Regarding the framers’ motivations for including the right to trial by jury in the Constitution, the United States Supreme Court has stated:

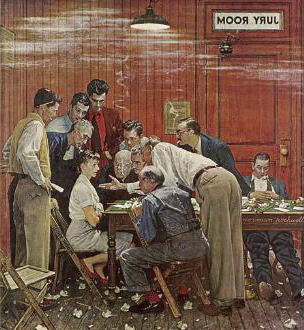

“The framers … strove to create an independent judiciary, but insisted upon further protection against arbitrary action. Providing an accused with the right to be tried by a jury of his peers gave him an inestimable safeguard against the corrupt or overzealous prosecutor and against the compliant, biased, or eccentric judge.” Duncan v. Louisiana.

Article III, Section 2, of the Constitution provides that “[t]he Trial of all Crimes, except in Cases of Impeachment, shall be by Jury.” Additionally, the Sixth Amendment states, “In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury ….” Similarly, the Seventh Amendment preserves the right to a jury trial in civil cases with an amount in controversy above twenty dollars. When the Constitution was adopted, English and American common law recognized several key facets of a jury trial. Common law dictated that the jury should consist of twelve jurors meant to serve as a cross-section of the public (at that time, however, only white men could serve as jurors), the court should instruct the jury on the applicable law, and the verdict should be unanimous. These facets were later codified by the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure and remain essential components of federal criminal jury trials.

Since the ratification of the Constitution, the Supreme Court has continued to shape the right to trial by jury. The Court has held that the right applies in all cases in which the maximum allowable sentence exceeds six months of imprisonment and a $1,000 fine. Baldwin v. New York. The Court has also held that a criminal defendant has a right to a jury trial not only on the question of guilt, but also on any fact used to increase the defendant’s sentence beyond the maximum permitted by applicable statute or sentencing guidelines. Blakely v. Washington; Apprendi v. New Jersey. Though juries were historically composed of white men, several landmark cases have helped to solidify the right to serve on a jury for women and racial minorities. Other decisions increased the diversity of jury pools, thus helping to ensure that juries throughout the nation represent a fair cross-section of the population.

The institution of the trial by jury has not gone without criticism. Some legal commentators have taken the position that jury trials cost the judiciary significant time and money and have resulted in a backlog of cases. Additionally, some countries have abolished trials by jury. For instance, the government of India abolished jury trials in 1960, based on concerns that the media and public opinion had a strong influence on juries. Similarly, Malaysia abolished jury trials in 1995 due to fears over the risks of placing the fate of an accused individual in the hands of untrained laymen. Proponents have countered that the trial by jury should not be measured merely in terms of expenses and time, but by its many benefits. In their view, juries provide a fundamental check on state power and serve as a means of injecting community norms, values, and morality into the justice system. They further counter that jury trials provide a meaningful way for citizens to participate in and learn about the administration of justice. To that end, Alexis de Tocqueville, a French political historian who studied the development of democracy in the United States, stated that jury service “rubs off that private selfishness which is the rust of society.”

Regardless of the controversy over the efficiency and benefits of the trial by jury, it continues to be a deeply rooted legal institution in the United States.