43. New Hampshire's "Fighting Fifth" Civil War Regiment

Located: 3rd floor, conference room inside Courtroom 4 vestibule

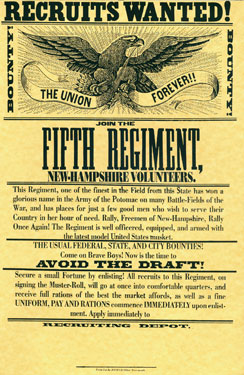

Prints in courthouse exhibit: Recruitment poster for N.H. Fifth Regiment Volunteers;

photograph of Fifth Regiment’s construction of the Grapevine Bridge over the Chickahominy River

in Virginia. (New Hampshire Historical Society)

New Hampshire’s “Fighting Fifth” Regiment fought in numerous battles throughout the Civil War, and earned a reputation for its tenacity and combat readiness. By the end of the Civil War, this regiment had suffered more dead and wounded men than any infantry or cavalry regiment in the entire Union Army.

New Hampshire’s “Fighting Fifth” Civil War Regiment

When President Abraham Lincoln called for the formation of troops to repel the southern insurrection, a patriotic fervor spontaneously swept through the Yankee north. Over the course of the Civil War, 31,650 New Hampshire men served in the Union Army, representing over ten percent of the state’s population.

Allegiance to the republic inspired the new enlistees; training, discipline and fraternity sustained them through their terms. The Fifth Regiment of New Hampshire Volunteers, organized in Concord with 1,012 men, perfectly illustrated these traits. The Fifth became known for its tough training, its battle readiness, and its strong and charismatic leader, Colonel Edward E. Cross of Lancaster. Colonel Cross instilled in his troops his own soldierly virtues: obedience to orders and a refusal to retreat. He fostered in them a determined loyalty to the Army, and they took his teachings to heart.

The regiment’s first substantial contribution to the war came on May 28, 1862, when they built the famed Grapevine Bridge, “passable for artillery,” across Virginia’s Chickahominy River and its swamp within just two days. Colonel Cross recalled the May 31st Battle of Seven Pines in his private journal: “Confederates had driven Casey’s Division from its camp and captured a large amount of property. The arrival of Sedgwick’s Division alone saved the army from disastrous defeat, and be it remembered Sedgwick’s Division crossed the Chickahominy swamp on the bridge of logs 70 rods [385 yards] long, built by the 5th New Hampshire Regiment! Let the impartial historian remember this.” Just a day later, the Fifth was in combat at the Battle of Fair Oaks. Casualties were high for the regiment; Colonel Cross himself was shot through the thigh. He returned to New Hampshire to recover from the injury. After just two weeks he had enlisted more soldiers and left to rejoin his men in Virginia. Colonel Cross went on to lead the regiment in numerous engagements, including the Seven Days Battles, Antietam (where he was again seriously wounded), Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, and finally, Gettysburg. The regiment, renowned for its valor and ability, earned the nickname the “Fighting Fifth.”

Colonel Cross was a colorful, courageous and brash figure who expected the bravest of conduct from his regiment in battle. He wore a red bandana around his head in combat so his men could easily spot him. Captain Thomas Livermore recorded this unconventional example of his leadership in the Battle of Antietam:

As the fighting grew furious the colonel cried out,

“Put on your war paint!” and looking around I saw

the glorious man standing erect with a red handkerchief,

a conspicuous mark, tied around his bare head and the

blood from some wounds on his forehead streaming

over his face, which was blackened with powder.

Taking the cue somehow we rubbed the torn end of the

cartridges over our faces, streaking them with powder like a

pack of Indians, and the colonel, to complete the

similarity, cried out, “Give ’em the war whoop!” and all

of us joined him in the Indian war whoop until it must

have rung out above the thunder of the ordinance. I have

sometimes thought it helped to repel the enemy by alarming

him to see this devilish-looking line of faces,

and to hear the horrid whoop; and at any rate,

it reanimated us and let him know we were unterrified.

Colonel Cross was especially proud of his “brave boys,” as reflected in his private journal, his personal correspondence, and in a poem he wrote to honor the “Fighting Fifth.” The poem, excerpted here, was composed during his recovery from injuries sustained at the Battle of Fredericksburg:

“Tramp and Hurrah for the Fifth”

Come gather around while the campfires are bright;

Let your voices go out on the wings of the night.

We’ve arms tried in battle and hearts without fear;

Let the rebels find in battle that the old Fifth, it is here.

And it’s tramp & hurrah for the fifth.

At Fair Oaks we formed in the silence of the night.

With Howard to lead us we opened the fight.

O, we entered the woods & with no one to aid,

We drove out & whipped a whole rebel brigade.

Again at Antietam we charged through the foe,

Their colors were captured their leaders laid low …

On the red field of Fredericksburg see us again,

As we faced the grape shot & the bullets like rain.

“Close up,” cried the Colonel. “Close up and fire low.

If you fall, die like men with your hearts to the foe.”

And it’s tramp and hurrah for the fifth …

The Battle of Gettysburg found Colonel Cross in command of the 1st Brigade, 1st Division of the 2nd Army Corps. It was the second day of battle at Gettysburg, and the Colonel wore a black bandana this time, sensing his impending death. He told his aide that Gettysburg would be his last battle and instructed him to deliver his private books and papers to his brother after the campaign. Despite his premonition the Colonel was “full of fire” as he readied his troops: “Gentlemen,” he said, “it looks as though the whole of Lee’s rebel army is right here in Pennsylvania; there will be a great battle fought today.” Late in the afternoon General Winfield S. Hancock rode up to him. “Colonel Cross, this day will bring you a star,” he stated. “No, General,” Cross calmly replied, “this is my last battle.” Shortly thereafter, having entered the woods next to the Wheatfield to fight alongside the men of his regiment, Colonel Cross was shot and mortally wounded by a rebel marksman. The men of the “Fighting Fifth” made sure to respond accordingly; as the colonel was taken to a field hospital, the sharpshooter was targeted and killed. Dying on the night of July 2, 1863, Cross expressed the thoughts of many in Gettysburg that day: “I did hope I would live to see peace and our country restored.”

The Fifth Regiment of New Hampshire Volunteers, reduced to fewer than 100 men after Gettysburg, again reinforced its numbers and returned to service. It remained active until the war ended, with nearly 2,600 soldiers passing through its ranks. Throughout the Civil War, the regiment sustained 1,051 casualties, including 473 deaths. It carries the unfortunate but honorable distinction of having suffered more dead and wounded men than any infantry or cavalry regiment in the entire Union Army.