41. The Presidency of Abraham Lincoln

Located: 3rd floor hallway, near Courtroom 4

Prints in courthouse exhibit: F.B. Carpenter, First Reading of the Emancipation Proclamation (1866); Jean Leon Gerome Ferris, The Gettysburg Address (c. 1900); Don Stivers, The Volunteers; Mort Kuntsler, Chamberlain’s Charge; copy of Lincoln’s handwritten speech at Gettysburg (November 19, 1863)

These two essays, Speaking of Freedom and Speaking of Sacrifice, tell of the political climate at the time of President Abraham Lincoln’s election, the eruption of civil war within weeks of his inauguration, and his course of action in the conduct of that war. Two significant events are highlighted: Lincoln’s issuance of an extraordinary military order, the Emancipation Proclamation, which freed the slaves in January, 1863; and his delivery of the Gettysburg Address, memorializing the famed July, 1863 battle and casting the war itself as a necessity in securing the fundamental ideals of the nation. This study considers these events in Abraham Lincoln’s presidency, as well as Lincoln’s understanding of both the Declaration of Independence and the United States Constitution, including the presidential oath to preserve the union of the states.

Essays

On the Presidency of Abraham Lincoln:

The Emancipation Proclamation

Speaking of Freedom

The Emancipation Proclamation, issued on January 1, 1863, spoke directly to more than three million southern slaves who would thereafter be freed as the Union Army advanced into Confederate territory. With this Act, President Abraham Lincoln effectively stole the strategic military advantage from the rebellious states and directed the nation toward realizing a core principle of the Declaration of Independence – that “all men are created equal.”

Many issues had challenged the nation’s journey toward what President Lincoln considered a “fundamental and astounding” result: The freeing of Confederate slaves. The Emancipation Proclamation dealt a fatal blow to slavery in the United States by its masterful conception within the bounds of the United States Constitution and the competing politics of the day.

A National Dispute

Abraham Lincoln was narrowly elected President in 1860, at a time of deep and vitriolic division among the voters. The country was rapidly expanding westward, presenting an already conflicted American population with new questions about the legitimacy of slavery. Ten years earlier, Congress had passed the Fugitive Slave Act, requiring the return of runaway slaves to their owners regardless where in the Union they were found. The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 rescinded the 1820 Missouri Compromise’s geographic limits on slavery, allowing new states to determine for themselves their free or slave-holding status. In 1857, the United States Supreme Court ruled in Dred Scott v. Sanford that people of African descent could never be citizens of the United States and, as a result, could make no claim to freedom. The longstanding abolitionist movement reacted with alarm, and many previously indifferent northerners were moved to oppose slavery. At the end of the decade, the anti-slavery Republican Party launched Lincoln into the middle of a furious showdown over slavery’s expansion into the western territories. “One section of our country believes slavery is right, and ought to be extended, while the other believes it is wrong, and ought not to be extended. This is the only substantial dispute,” the new President said at his inauguration. It was certainly substantial.

Abraham Lincoln’s opposition to slavery was well known. He had publicly condemned the inconsistency presented by a nation gloriously founded on principles of liberty and equality that permitted the ownership of slaves. In 1854 he had decried the Kansas-Nebraska Act’s effect on the spread of slavery. “I hate it,” he said, “because of the monstrous injustice of slavery itself, … [Because it] causes the real friends of freedom to doubt our sincerity, and especially because it forces so many really good men … into an open war with the very fundamental principle of civil liberty – criticizing the Declaration of Independence.” He believed that America would one day have to directly confront the clash between free states and slave states. “‘A house divided against itself cannot stand,’” he had said in 1858. “I believe this government cannot endure, permanently half slave and half free. I do not expect the union to be dissolved – I do not expect the house to fall – but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing, or all the other.”

Lincoln recognized the constitutional restraints against federal action to abolish slavery in the states. Nonetheless, southerners were unconvinced by assurances that his new administration would leave them alone. They feared that federal anti-slavery policies would isolate and severely damage their robust economies, and that the addition of new free-states would undermine their national political influence. Indeed, the President hoped to persuade the southern states to agree to end slavery in return for federal compensation. This approach depended on containing the number of slave-holding states. If free-states were outnumbered, Congress could not be expected to approve policies encouraging slavery’s demise. Therefore, President Lincoln intended to push hard against its western expansion.

Civil War

By the time Lincoln took office on March 6, 1861, an active rebellion was underway. In response to his election seven states had already seceded from the Union to form the Confederate States of America. With their April 12th attack on Fort Sumter in South Carolina, defense of the Union became the President’s singular focus. Despite slavery’s predominance as a cause for the South’s rebellion, efforts to thwart its practice would have to wait. “We didn’t go into the war to put down slavery, but to put the flag back”, Lincoln stated in 1861.

Over the first two years of war, the Union suffered repeated defeats, in part because the Rebel army fought with the advantage of slave labor working on its home front. Northerners voiced louder support for freeing slaves as it became apparent that slave labor provided essential support to the South. Abolitionists continued to forcefully push the moral agenda, and President Lincoln was regularly criticized for failing to wrest the slaves from the grip of the enemy. Meanwhile, the Confederacy hoped to pull the slave-holding border states that remained in the Union (Delaware, Maryland, Missouri and Kentucky) to their side. President Lincoln sought a solution that would neither risk these states’ allegiance to the Union nor violate the Constitution. To that end, Lincoln obtained a congressional pledge to compensate any slave-state that would voluntarily “adopt a gradual abolishment of slavery,” and directly appealed to the border states in the spring of 1862. “[W]hile the offer is equally made to all, the more northern shall by such initiation make it certain to the more southern that in no event will the former ever join the latter in their proposed confederacy,” Lincoln explained to Congress. On July 14, however, the border states’ congressional delegations resoundingly rejected that offer.

A Military Order of Freedom

Waging a lengthy and brutal civil war to protect the United States from dissolving over the question of slavery finally demanded that action be taken against the institution itself. The President concluded that while neither he nor Congress could ban slavery by law or edict, he could do so as an essential military measure against the enemy. Drawing from his authority as Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces during war time, Lincoln drafted an extraordinary military order to free the slaves. On July 22, 1862, he presented the Emancipation Proclamation to his Cabinet, as captured in this painting by F.B. Carpenter. He sought no one’s approval, however, as his mind was made up. The Emancipation Proclamation was issued in two stages. Lincoln’s preliminary decree announced his intention for compensation to be paid to slave-holding states if they would return to the Union and voluntarily agree to abolish slavery. But then came an ultimatum: In the event that they would not surrender by January 1, 1863, “all persons held as slaves within any State … the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.”

Saving the Union and freeing the slaves were now forever linked as essential purposes in prosecuting the war. Despite the clear warning of the preliminary decree, the Confederacy held fast to the rebellion. In December of 1862, President Lincoln addressed Congress: “Fellow citizens, we cannot escape history,” he said. “We say we are for the Union…. We know how to save the Union…. In giving freedom to the slave, we assure freedom to the free – honorable alike in what we give, and what we preserve. We shall nobly save, or meanly lose, the last best hope of earth…. The way is plain, peaceful, generous, just – a way which, if followed, the world will forever applaud, and God must forever bless.”

On January 1, 1863, Abraham Lincoln formally signed the Emancipation Proclamation. In this final order, the President named the states and parts of states that were currently in rebellion and boldly proclaimed their slaves to be free. He then made it clear that the military and naval forces of the United States would respect and maintain the freedom from servitude of the freed slaves. In the last clause of the Proclamation he confidently described it as “an act of justice, warranted by the Constitution, upon military necessity.”

As a military order, the Proclamation did not apply to the non-rebellious border states and the parts of Confederate states already under Union control. But it provided for actual and immediate freedom to slaves held in rebel territory as the Union Army advanced.

The Emancipation Proclamation fundamentally changed the character and course of the ongoing war. While it was controversial among those Union soldiers and officers who believed more in preserving the Union than in freeing the slaves, it gave many a new and honorable sense of purpose. The Confederacy’s war effort was weakened as the Union Army exacted the rebels’ loss of slave labor. Further, the Proclamation specifically allowed black soldiers to fight for the Union. One hundred and eighty thousand eventually did so, making a very substantial contribution to the effort. Abraham Lincoln had fused together his determined loyalty to the nation’s founding principles, his duty to preserve the Union, and his desire to extinguish the abhorrence of slavery. But the military order would have no permanent legal effect once the Civil War ended. After issuing the Proclamation, President Lincoln worked to secure the passage of a Constitutional Amendment to abolish slavery throughout the entire United States. Two years later, on January 31, 1865, the United States House of Representatives passed the Thirteenth Amendment, which Lincoln signed before it went to the states for ratification. All slaves were finally freed by the formal adoption of the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution in December, 1865.

On the Presidency of Abraham Lincoln:

The Gettysburg Address

November 19, 1863

Speaking of Sacrifice

President Abraham Lincoln delivered his most famous speech at a ceremony to dedicate the new Soldiers’ National Cemetery on a scarred and mournful battlefield in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Just four months had passed since the horrific fight between more than 160,000 Union and Confederate soldiers claimed 51,000 dead, wounded and missing, marking the Battle of Gettysburg as the largest and bloodiest of the Civil War. Twenty-six square miles of pristine farm country had been involved, much of it devastated and still littered with the remnants of war. There had been little cheering for the Union victory at Gettysburg; the toll of the dead and gravely wounded, along with the survivors’ physical and emotional exhaustion after three intense days of battle, had too vividly underscored the awful reality of the continuing conflict.

The Civil War had already defined Abraham Lincoln’s presidency. It was his constant burden. Even as he took the oath of office on March 4, 1861, seven southern states had recently claimed secession from the nation, convinced that their slave-labor economies would suffer under the new administration. President Lincoln had devoted his inaugural address to urging a peaceful reconciliation with his “dissatisfied fellow countrymen,” promising that the government would not attack them. “We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies,” he implored. Regarding the essential duties of his new office, however, he expressly contemplated “the momentous issue of civil war,” warning against their aggression. “You have no oath registered in Heaven to destroy the government,” he pointed out, “while I shall have the most solemn one to ‘preserve, protect and defend’ it.”

Just five weeks later, the Confederacy attacked Fort Sumter, dashing all hope for a peaceful resolution of the matter. President Lincoln immediately cast the conflict as a test of the durability of the constitutional democracy established by the American Revolution. In his July 4, 1861, message to Congress, he commented on the national democratic experiment, noting that it had so far been successfully established and successfully administered. Whether it could be successfully maintained “against a formidable attempt to overthrow it” would now be determined. Defending the Union, he said, would “demonstrate to the world that those who can fairly carry an election, can also suppress a rebellion – that those who cannot carry an election, cannot destroy the government. – that ballots are the rightful, and peaceful, successor of bullets…. Such will be a great lesson of peace, teaching men that what they cannot take by an election, neither can they take by a war….” However, no one expected the prolonged and difficult campaign that followed. Two years later, in the summer of 1863, an unpopular Union military draft took effect as overall support of the war effort waned. Already claiming more than a quarter million casualties, the war had so roiled the young nation and so consumed its people, that the President’s mere words of consolation in dedicating the Soldiers’ National Cemetery at Gettysburg would surely be inadequate.

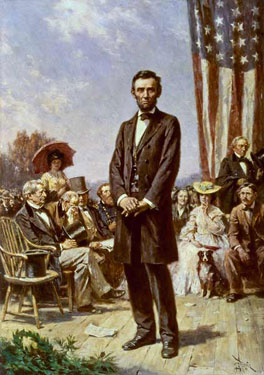

President Lincoln was not the featured speaker at Gettysburg, but had been invited to close the ceremony with “a few appropriate remarks […] after the Oration.” Respectfully and without pretense, President Lincoln prepared a speech of just 272 words. He was determined to keep it “short, short, short.” Taking the podium after a two-hour formal address by the renowned speaker and politician Edward Everett, the President pulled the penned and penciled draft from his coat pocket and spent just the next two minutes in its delivery.

The Gettysburg Address is extolled not only for its succinct and eloquent construction, but for its effective turning of the occasion from a regretful remembrance to a solemn recommitment of energy and purpose to the cause of freedom. At a time of unparalleled grief and strife, President Lincoln evoked the idealism of the young nation’s founders. He heralded the soldiers’ sacrifices for the survival of that nation of promise. He deftly and respectfully deferred all attention away from his official importance and toward the “unfinished work … so nobly advanced” by the honored dead. By his own humility, the President was able to present the soldiers’ cause “that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth,” as clearly worthy of the nation’s re-doubled efforts.

It is likely that few in the crowd of 15,000 actually heard much of the masterfully crafted speech. Those who were present were unprepared for it to end so quickly, and its significance was not immediately recognized. The essence of the speech, however, was soon appreciated as an important restatement of the war’s necessity, reviving the Union’s commitment to victory. The President was asked for copies of his text, which he graciously re-wrote for several friends. Edward Everett, whose speech preceded President Lincoln’s, wrote to President Lincoln the next day, “I should be glad, if I could flatter myself that I came as near to the central idea of the occasion, in two hours, as you did in two minutes.”

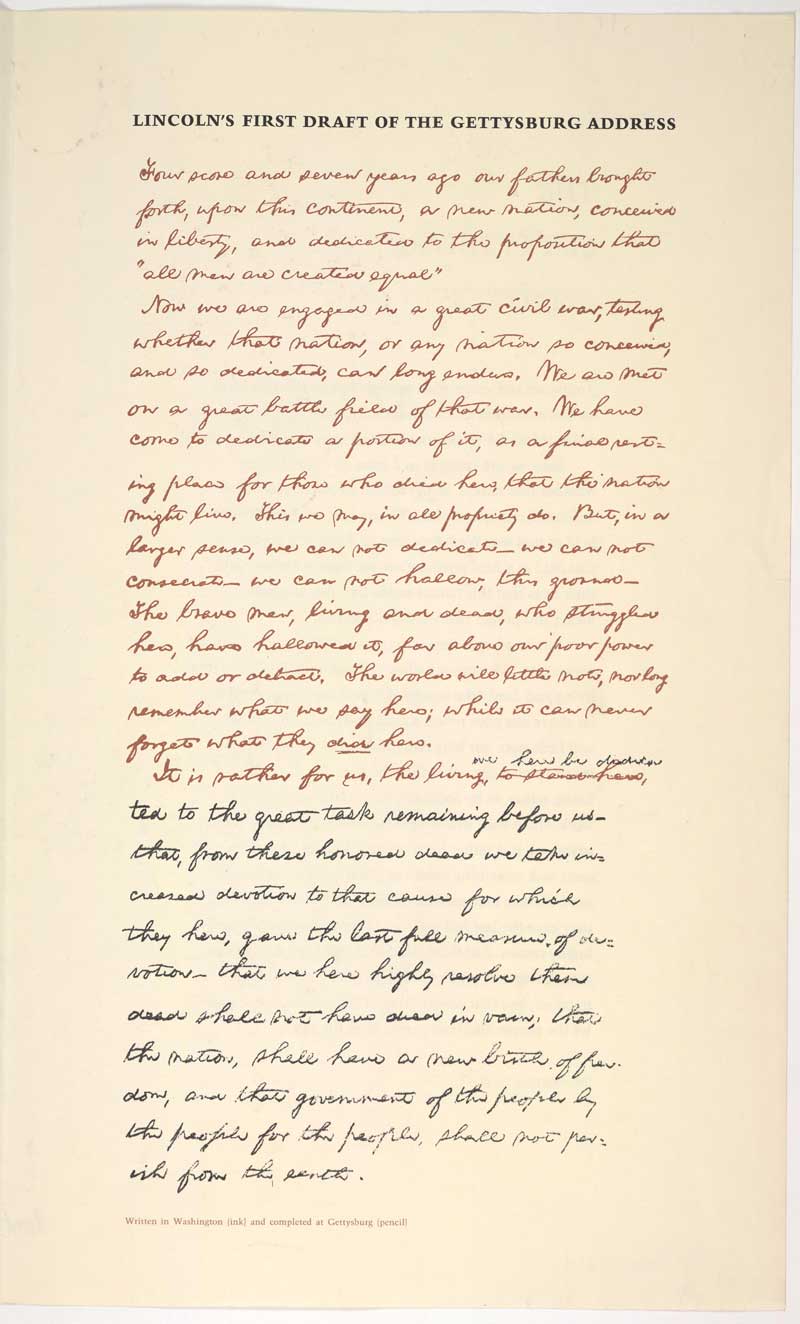

The Gettysburg Address is known as one of the greatest and most often quoted speeches in history. The re-printed version displayed here is engraved upon the wall of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. This handwritten copy is believed to have been the script from which President Lincoln read, with some ad-libbing, at Gettysburg.

Although two more tumultuous years of civil war ensued, historians agree that Gettysburg was a major turning point in favor of the Union forces. President Lincoln’s determination to preserve the Union and the ideals of the nation’s constitutional democracy ultimately proved victorious with General Robert E. Lee’s surrender of his Confederate troops at Appomattox, Virginia on April 9, 1865.