38. Declaration of Independence

Located: 3rd floor hallway, near Courtroom 2

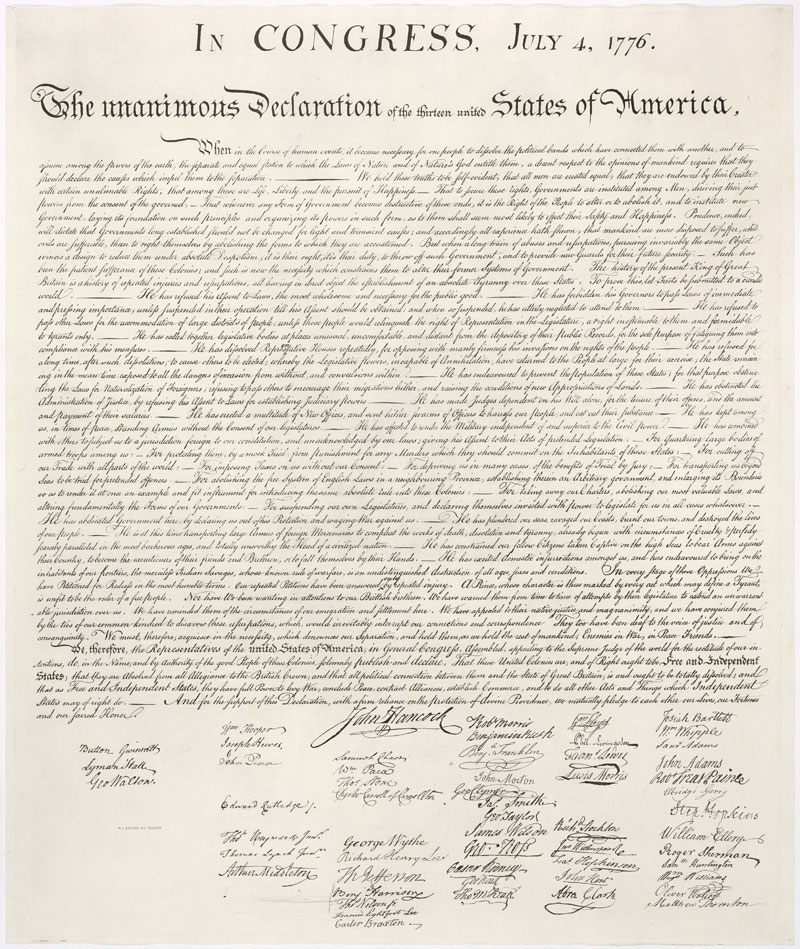

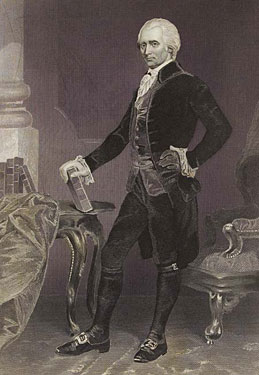

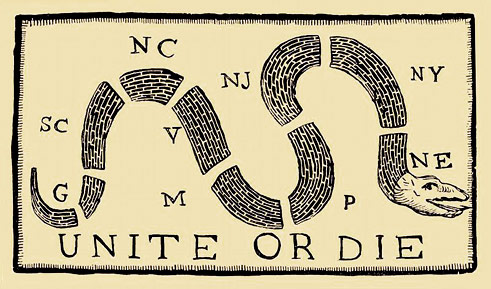

Prints in courthouse exhibit: Variation of Benjamin Franklin’s 1754 “Join or Die” illustration; Thomas Jefferson’s draft of the Declaration; Declaration of Independence broadside; John Trumbull’s painting, Declaration of Independence; William Walcutt’s painting, Pulling Down the Statue of King George III at Bowling Green in Lower Manhattan; Portrait of Richard Henry Lee

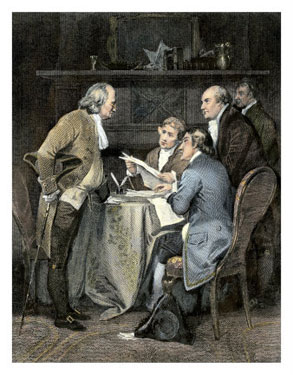

Other image of interest: Alonzo Chappel, Drafting the Declaration.

This exhibit explores the circumstances and political process by which the thirteen colonies became united in their opposition to continued British rule. The brief study recounts the radicalization of the delegates to the Second Continental Congress (1775 -1776) under the essential leadership of Richard Henry Lee of Virginia. Lee’s Resolution, calling for total independence from the mother country, signaled the beginning of a new political reality: just 25 days later, on July 2, 1776, the measure was voted and approved. By July 4th, after considerable congressional editing of Thomas Jefferson’s draft, a formal Declaration of Independence was approved for signing, and was presented to the people of the new United States of America.

The Declaration of Independence

Between 1688 and 1763, the early American colonies enjoyed “Salutary Neglect:” an informal British policy that avoided strict enforcement of Parliamentary laws in North America. During this time, the colonists lived independently from British governing authorities. Local assemblies exercised political autonomy over their internal affairs. American and Dutch merchants negotiated lucrative trade agreements. Urban merchants and southern plantation owners became the leaders of a new American aristocracy. Americans began to develop a cultural identity that was rooted in freedoms and personal liberty.

By 1763, the French and Indian War had ended and Britain’s national debt had more than doubled. Parliament expected the American colonists to help shoulder the financial burden by paying taxes on everyday household goods such as paper, lead, sugar, and tea. Although they paid significantly less than subjects living in Great Britain, the colonists reacted strongly. Fearing the loss of their liberties, they boycotted and even destroyed British goods while exclaiming, “no taxation without representation.” (The colonies had “virtual representation” in Parliament; however, most virtual representatives had never even been to North America.) As punishment for the protests, the Coercive Acts stripped colonists of what they most sought to protect; any local governmental positions they had once held were replaced by Royal officials.

The First Continental Congress (Philadelphia, 1774), attended by fifty-six representatives from twelve of the thirteen colonial assemblies, met to establish a boycott agreement for British goods. It was an important step toward reasserting control over their commerce. Most importantly, the First Continental Congress made provisions for the Second Continental Congress that would convene on May 10, 1775. Intervening violence in Concord and Lexington, Massachusetts; Williamsburg, Virginia; and Newcastle, New Hampshire inspired new and more radical action from the Second Continental Congress: complete and irrevocable independence from Great Britain.

While the New England delegates to the Congress all strongly advocated independence, other influential figures such as Philadelphia’s favorite son Benjamin Franklin and hot-blooded Virginian Richard Henry Lee actively lobbied support for the cause. More colonies still remained opposed to independence than in agreement. To persuade those colonies to abandon their hopes of reconciliation with Britain, strong leadership was required from a colony outside of New England. The Virginians were the obvious leaders. George Washington had already been elected Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army. Richard Henry Lee was a member of one of Virginia’s oldest and most prominent families and was as passionate about independence as New England’s ring leader, John Adams. Virginia itself was the most influential colony in Congress: the wealthiest, most socially powerful, and largest geographically. Virginia’s leadership changed the fight for independence from an essentially regional to a genuinely national movement.

Lee was a born orator. He was confrontational by nature and possessed a fiery and rebellious spirit. His reputation and character made him the perfect liaison between the New Englanders, the Virginians, and the colonial delegates from the more temperate southern and middle colonies. There was only one problem. Virginia’s revolutionary government had not authorized their Congressional delegates to support American independence. In the spring of 1776, Lee left the Second Continental Congress to attend the Fifth Virginia Convention in order to persuade it to support independence. The vote for independence was unanimous, and the official proposal became known as the “Lee Resolution.”

The Lee Resolution

Resolved—that these colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent states, that they are absolved of all allegiance to the British Crown and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved.

That it is expedient forthwith to take the most effectual measures for forming foreign Alliances.

That a plan of confederation be prepared and transmitted to the respective Colonies for their consideration and approbation.

Lee raced back to Congress, and on June 7, 1776, he presented the Lee Resolution. Debates on the proposal raged for four days. Those in opposition, led by Philadelphian John Dickinson, insisted that the Congress hold out for reconciliation and in the meantime appeal to foreign powers for monetary and military aid. Supporters argued that those wealthy European powers had their own colonies in the New World and would not come to the aid of a colony in “open and avowed rebellion.” An independent nation fighting for their country not against it would be more likely to receive that aid.

On June 11, 1776, after several colonies threatened to walk out of Congress, Congressional President John Hancock postponed debate to allow the delegates to seek new instructions from their individual legislatures. On that same day, a “Committee of Five” was appointed to draft a declaration should Congress pass the Lee Resolution. The following is an excerpt from the Journals of the Continental Congress:

Resolved, That the committee, to prepare the declaration, consist of five members: The members chosen, Mr. [Thomas] Jefferson, Mr. J[ohn] Adams, Mr. [Benjamin] Franklin, Mr. [Roger] Sherman, and Mr. R[obert] R. Livingston.

The young Virginian, Thomas Jefferson, was selected as the primary writer by his fellow committee members. Adams insisted that Jefferson was the better writer, “and a Virginian should be at the head of this business.” Adams also perceived himself to be “obnoxious, suspected, and unpopular [and Jefferson] very much the opposite.” The Congress was more likely to accept independence if it came from the silent and pensive Jefferson instead of the blustery Adams or even the whimsical Franklin.

Jefferson’s draft did not express anything that the colonists had not heard before. He drew heavily from notable philosophers, politicians, and legal minds of the day including George Wythe, his law professor and mentor. But by far the largest influences were two seventeenth century English philosophers: Thomas Hobbes and John Locke. Both Hobbes and Locke were strong advocates of social contract theory: a reciprocal relationship between the government and the governed centered on “natural rights” or “divine rights.” Their belief was that a government’s authority derived from the consent of the governed. If that authority became corrupt or violated their natural rights, the people were free to reject the government and establish one of their own design. Because these ideas were popular and widely accepted in British North America by 1776, independence became the next logical step for the colonies.

The Committee members met to collaboratively edit the draft. Franklin was more practical and less philosophical than Jefferson, who wrote with a lofty and poetical grace. It was Franklin who altered “we hold these truths to be sacred and undeniable” to “we hold these truths to be self-evident,” because he wanted the declaration to only make assertions of reason, not religion. According to Franklin, the phrase sacred and undeniable “smack[ed too much] of the pulpit.”

On July 2, 1776, Congress reconvened to vote on the Lee Resolution. During the recess, almost every colony that had opposed independence changed its position. The most stalwart opponent, John Dickinson of Pennsylvania, was not present. He left the vote to his colony’s remaining pro-independence delegates. The Lee Resolution passed with twelve votes and one abstention (New York never received instructions from its colonial legislature and therefore declined to vote). The former British American colonies were now united American states.

For the next two days, Congress dissected Jefferson’s declaration. Over a quarter of the original material was removed, including all references to slavery. More than a third of the congressional delegates owned slaves, including Lee, Dickinson and Jefferson. Even New Englanders who opposed slavery recognized that it was beneficial to their shipping industries. They did not push the issue because they feared efforts to abolish slavery would jeopardize the hard-won support for independence. On July 4, 1776, Congress approved the final draft of the Declaration of Independence. Over the next two months, delegates signed their names as they passed through Philadelphia.

The Declaration served its purpose. It legitimized the rebellion in the eyes of the public and legally separated the American colonies from Britain. Essential foreign support for the Revolutionary War came from France and Spain. In the Congress, attentions shifted to the creation of a new American republican government. Across the young nation, a new “Spirit of `76” was born.

The featured work by artist William Walcott depicts the citizens of Manhattan tearing down the statue of King George III that once stood in Bowling Green Park, Lower Manhattan. While the artist took some creative liberties, this event actually occurred on July 9, 1776. Just as ordinary Americans—farmers, lawyers, writers, tradesmen—created the possibilities of a new world, others rose to bring it forth. Ever since, this new system of republicanism, deeply rooted in the Declaration of Independence, has inspired the American people to uphold its assertions of equality and promises of freedom.

Drafting the Declaration - (Alonzo Chappel)

Richard Henry Lee - (Alonzo Chappel)

Variation of Ben Franklin's 1754 "Join or Die" illustration

Declaration of Independence - (John Trumbull)

Pulling Down the Statue of King George III at Bowling Green in Lower Manhatten - (William Walcutt)