32. Washington's Troops and the Battle of Trenton

Located: 3rd floor hallway, near Courtroom 1

Prints in courthouse exhibit: Emanuel Leutze, Washington Crossing the Delaware (1851); Excerpts from Thomas Paine’s text, The Crisis, 1 (1776)

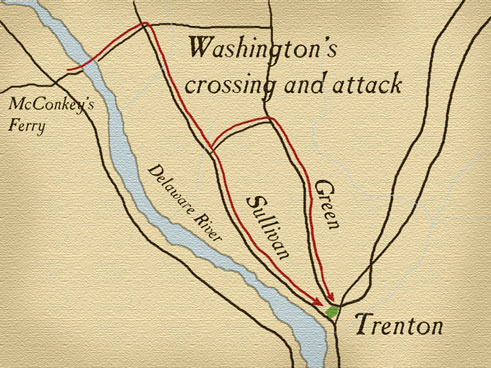

Other image of interest: Map of the advance on Trenton

The enormous challenges ahead of the newly formed Continental Army were immediately evident to General George Washington. This essay follows Washington’s troops as they lose battles in New York and retreat in the cold to Pennsylvania, where they await reinforcements. The men lacked supplies, and were generally tired, discouraged and hungry. The British occupied Rhode Island and New Jersey, and Philadelphians were fleeing their homes in fear. When reinforcements from New England arrived, General Washington’s ambitious plan to take Trenton was put into action. (Noted in the essay: both John Sullivan and John Stark of New Hampshire, and troops under their commands, took part in the river crossing and the Battle of Trenton.)

Emanuel Leutze’s famous depiction of the men crossing the Delaware River on Christmas night, 1776, captures the emotion and fury of the event, if not its historical accuracy. The exhibit considers the significance of the crossing and the ensuing Battle of Trenton. It also features excerpts of Thomas Paine’s work, written while encamped with Washington’s troops, and published in order to rally essential support for the Revolution.

Essays

Washington’s Troops and the Battle of Trenton

Fledgling Independence

The colonists’ resistance at Boston Harbor and the Battles of Lexington, Concord and Bunker Hill had energized the revolutionary spirit in 1775. In a time of great optimism for the budding Republic, the Declaration of Independence was drafted, approved and finally signed on July 4, 1776.

Soon enough, however, the challenges ahead were evident. Full-scale war became inevitable as the mighty and impressive British army and naval forces assembled in great numbers. General George Washington doubted the abilities of the farmers, seamen and common laborers he commanded, but had no time to implement the structure and training of a professional military force. The disorganized and undisciplined American regiments and militias which formed the new Continental Army were about to be tested.

Early Action

After the British left Boston Harbor in defeat, New York and its large group of loyalist supporters was the obvious focus of their intentions. General Washington and his military leaders faced the difficult task of fortifying the islands, harbor and waterways of New York City. By July 1, 1776, thousands of British Regulars had already amassed at Staten Island. Over the next six weeks their ranks soared to over thirty-five thousand, including ten thousand hired German Hessian troops. Ten thousand British sailors brought thirty battleships and three hundred supply ships into New York Harbor.

Exhausted American soldiers remained on high alert at all times. With Continental forces divided to defend vital points in and around New York City, the British commanders finally launched a massive strike on Long Island at the end of August, 1776.

The Americans were far out-numbered and quickly overpowered. The loss was devastating: about three hundred patriots were killed and over one thousand were taken prisoner. Among the captured was Major General John Sullivan of New Hampshire, who led the northern flank near Long Island’s Brooklyn Heights. General Sullivan was soon released on the condition that he carry an offer of negotiation to Congress. But the American leaders no longer trusted the British, especially upon hearing about their mistreatment of prisoners on Long Island. There was no possibility of negotiating an end to this war.

General Washington daringly saved his remaining forces by managing a secret, fog-covered evacuation across the East River to Manhattan. Within weeks, however, New York City itself was in enemy hands. The autumn brought more misery to the Americans, who lost the fierce Battle of White Plains in late October and both Fort Washington and Fort Lee on the banks of the Hudson in mid-November. General Washington was forced to retreat to Pennsylvania, marching three thousand defeated men through New Jersey with the British in close pursuit.

December 1776

The situation in early December was bleak. General Washington’s remaining troops lacked blankets, shoes and clothing; they were tired, discouraged, hungry and cold. Many were sick, rendering them unfit for battle. While the weakened army awaited reinforcements in Pennsylvania, word came that Rhode Island had also fallen to the invaders. New Jersey suffered under the occupation of the British. Fear gripped the city of Philadelphia, and people of the area fled their homes. General Washington knew that more than a thousand of his remaining soldiers were sure to leave once their enlistments were up at the end of the year.

After long marches from the north, General John Sullivan and more than two thousand men reached the main army on December 20th. With his New England reinforcements in place, General Washington decided it was time to take action. Late on Christmas Eve, he met with his war council, made up of eleven officers including both General Sullivan and Colonel John Stark of New Hampshire. A pre-dawn attack on Hessian troops stationed in Trenton was planned for the day after Christmas. The fight was on!

The Crossing

Two thousand four hundred patriot troops arrived at the Delaware River near McConkey’s Ferry at eleven o’clock on Christmas night. The men had been marching for five hours, straight into a winter nor’easter. Boats of all sizes were ready at the river’s edge, many having been hidden for weeks along the shore pursuant to Washington’s orders.

The wind howled, and sleet and snow pelted the near total darkness. The men worked through the storm, loading heavy artillery and frightened horses onto ferries. Barely able to see the water before them, sailors from the Marblehead, Massachusetts regiment and the Pennsylvania Navy fought the fast moving, icy waters to deliver troops and cargo across the river, then returned to get more.

Very few eighteenth-century Americans knew how to swim, making the task even more daunting. Some fell overboard, requiring scrambled, frantic rescues. As each boat made it across, the men took turns chopping ice away from the shore to ease the unloading of the next arrival.

The severe weather had slowed the crossing and made a pre-dawn attack on Trenton impossible. After several harrowing hours, the frozen, exhausted army regrouped and prepared to march on. It was already four o’clock in the morning.

“Press on, Press on, boys!” shouted George Washington as the troops marched over rough terrain, ever closer to Trenton. He had lost the opportunity to strike before sunrise, but he knew it was too late to go back. At least the darkness of the storm would cover their approach.

The Battle of Trenton

The commanders split the advancing army into two columns. General Washington and General Nathaniel Greene of Rhode Island led men to attack the Hessian garrison from the north. General Sullivan brought Colonel Stark’s New Hampshire brigade and other troops in on the river road, to attack from the west. Because they had not heard from the Pennsylvania and New Jersey militias, which had tried but failed to cross the ice-jammed river south of Trenton, some of General Sullivan’s troops were ordered to rush through Trenton to secure the east side of town.

At 8:00 a.m. the battle was underway. Everything depended on a quick, decisive victory for the Americans. The small Continental army, having already endured a number of defeats, had to establish its worth. If they failed here, the American Revolution could well have been over.

This time the hard-fought battle was won. America’s soldiers, exhausted but determined, served with great valor and purpose. They managed to surprise the enemy and direct the fierce fight. Towards the end, General Sullivan’s men forced Hessian troops from the Assunpink Bridge, thwarting the escape of hundreds of enemy soldiers.

In all, one hundred and five Hessians were killed or injured, and eight hundred ninety-six taken as prisoners. Losses on the American side were, in General Washington’s words, “very trifling indeed, only two officers and one or two privates wounded.” (One of the wounded was future president James Monroe). General Sullivan boasted that his Yankees fought “exceedingly well.”

The victory at Trenton was a significant turning point for both the Continental Army and the nation. Hundreds of men were inspired to stay on with the army beyond their terms of service. The patriots matched their win with a decisive victory at Princeton the following week. With the boost in troop morale and battlefield success, General Washington could look forward to receiving many new recruits and far-reaching support for a revitalized War of Independence.

“Victory or Death”

General George Washington understood the value of a surprise attack, and he took precautions to conceal the details of his plan for Trenton. He chose a fitting secret password for his commanders, and put it in writing for each.

Congressman Benjamin Rush met privately with General Washington on the morning before the Delaware River crossing, and unknowingly discovered the chosen password. He recalled, “While I was talking to him, I observed him to play with his pen and ink upon several small pieces of paper. One of them by accident fell upon the floor near my feet. I was struck with the inscription upon it. It was ‘Victory or Death.’”

This manifesto defined the Revolution, and the spirit of the patriots who led troops into battle. Those from New Hampshire were no exception. General John Sullivan is said to have been captured on Long Island after a gun fight on horseback, attacking the enemy with a pistol in each hand. Once released, he immediately rejoined the revolutionary forces, eager to again brave the battlefield. At Trenton, Colonel John Stark (later promoted to General) ordered his battalion to charge through the storm with fixed bayonets, a fearsome sight which prompted the astonished Hessian pickets to abandon their posts. Colonel Stark had trained and armed his men with bayonets, not yet a part of the Continental Army’s conventional skills, matching his personal reputation as a tenacious fighter. His devotion to the Revolution resonates across his native state to this day, as he penned the phrase “Live Free or Die.”

Tyranny had ignited the cause of liberty. It had seared a new, pure and deep dedication to the ideal of freedom in the hearts of the American patriots. Echoing Patrick Henry’s famous cry, “Give me liberty or give me death,” General Washington had prepared the Continental Army to “resolve to conquer or die.” Despite their hardships and losses of 1776, the patriots had remained resolute. The Continental Army’s unlikely success in crossing the Delaware River to face the enemy at Trenton reflected the passionate commitment of leaders who, under the most difficult circumstances of war, pressed on. For the heroes of the American Revolution, liberty was a cause worth dying for.

About the Painting

Emanuel Leutze (1816-1868)

Washington Crossing the Delaware, 1851

Oil on canvas (149x255in.); Metropolitan Museum of Art

In this world-renowned painting, future presidents General George Washington and Lieutenant James Monroe (holding the flag) are prominently depicted while crossing the Delaware River on Christmas night, 1776. Artist Emanuel Leutze also included several figures, not personally identifiable, representing the diverse group of patriots who took part in the crossing.

Judging by their hats and clothing, we see an African New England seaman, a Scottish immigrant, two western riflemen in the bow and stern, three farmers, and one soldier each from the Delaware and Maryland regiments. The oarman in the red shirt is a purely generic figure.

Additional boats in the background contain men, horses and cannon on this perilous attempt to cross the river. Leutze captured a scene of action and fury as 2,400 troops managed their way to shore in a swift current of icy water.

In many ways this painting is inaccurate. The infantry actually crossed at night, in a severe storm of rain, sleet and snow. They stood in Durham cargo boats with high sides and icy water at their feet. The horses and artillery were loaded onto larger ferries. The “Betsy Ross” version of the flag would not have been present with the army at the time of the crossing. Finally, General Washington himself was just 44 years old in 1776, not yet bearing this older and more familiar presidential profile.

The artist’s creative use of light, detailing and symbolism results in a masterful portrayal of this historic event. The painting vividly conveys the emotion, patriotism and determination of the men involved in the crossing and the ensuing battles for America’s independence.

THE CRISIS.

I.

THESE are the times that try men’s souls.

The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of their Country; but he that stands it now, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman. Tyranny, like hell, is not easily conquered; yet we have this consolation with us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph.…

Britain, with an army to enforce her tyranny, has declared that she has a right (not only to TAX) but “to BIND us in ALL CASES WHATSOEVER,” and if being bound in that manner, is not slavery, then is there not such a thing as slavery upon earth. Even the expression is impious; for so unlimited a power can only belong to God.…

I have as little superstition in me as any man living, but my secret opinion has ever been, and still is, that God Almighty will not give up a people to military destruction, or leave them unsupportedly to perish, who have so earnestly and so repeatedly sought to avoid the calamities of war, by every decent method which wisdom could invent.…

I shall not now attempt to give all the particulars of our retreat to the Delaware; suffice it for the present to say, that both officers and men, though greatly harassed and fatigued, frequently without rest, covering, or provision, the inevitable consequences of a long retreat, bore it with a manly and martial spirit. All their wishes centred in one, which was, that the country would turn out and help them to drive the enemy back .…

I call not upon a few, but upon all; not on this state or that state, but on every state: up and help us; …

Let it be told to the future world, that in the depth of winter, when nothing but hope and virtue could survive, that the city and the country, alarmed at one common danger, came forth to meet and to repulse it.…

Not all the treasures of the world, so far as I believe, could have induced me to support an offensive war, for I think it murder; but if a thief breaks into my house, burns and destroys my property, and kills or threatens to kill me, or those that are in it, and to “bind me in all cases whatsoever” to his absolute will, am I to suffer it? …

By perseverance and fortitude we have the prospect of a glorious issue; by cowardice and submission, the sad choice of a variety of evils -- a ravaged country -- a depopulated city -- habitations without safety, and slavery without hope….

Look on this picture and weep over it!

and if there yet remains one thoughtless wretch who believes it not, let him suffer it unlamented.

COMMON SENSE.

-Thomas Paine

December 1776

About the Text

The Crisis was a series of sixteen essays published as pamphlets and in newspapers from 1776 to 1783. Thomas Paine, the author, had published Common Sense, a pamphlet credited with rallying essential support for American Independence, in January 1776. He closed the above excerpted essay, composed in December of that year, with the same designation.

Paine was with the Continental Army in New York, on their retreat through New Jersey, and at camp in Pennsylvania. He wrote The Crisis No. 1 at the lowest point of the campaign, when the troops were dispirited, their numbers dwindling, and their prospects of success fading. General Washington found this essay so moving that he ordered his officers to read it aloud to the men before the Delaware River crossing.

The Crisis No. 1 was first printed in Philadelphia on December 19, 1776, and published as a pamphlet on December 23, 1776. Thomas Paine wrote in language the common man of the times could understand, and these works were widely read. In addition to motivating patriotic resistance, the author intended to shame neutrals and Loyalists toward the revolutionary cause.