27. The Signing of the United States Constitution

Located: 1st floor, common area in Cleveland Federal Building

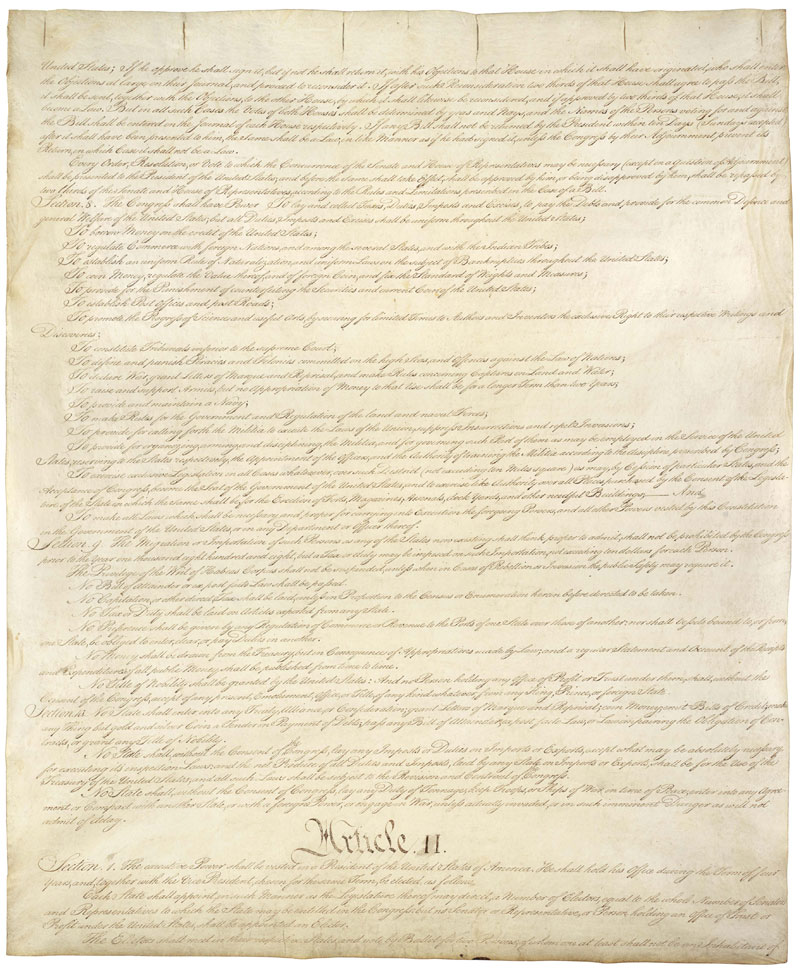

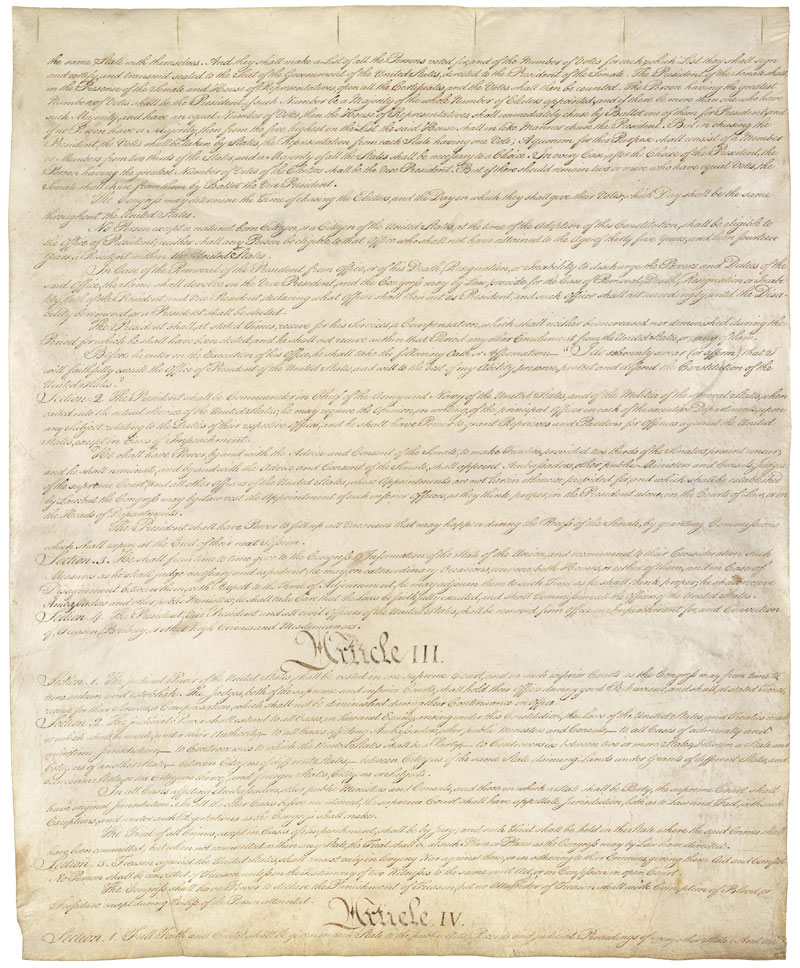

Print in courthouse exhibit: Howard Chandler Christy, Scene at the Signing of the Constitution of the United States (1940)

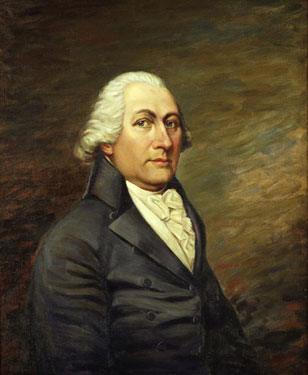

Other images of interest: Portraits of John Langdon and Nicholas Gilman, delegates to the Constitutional Convention

Christy’s famous original rendition of the September 17, 1787 signing of the Constitution hangs in the United States Capitol Building. It was painted with great attention paid to detail and accuracy: The artist visited Independence Hall in Philadelphia at the same season and time of day as the historic event, intending to replicate just how the light would have filtered into the room from the outdoors. He copied many of the delegates’ faces from original portraits. The delegates’ clothing, the furniture and drapes, and the extraneous items included in this painting were all researched to ensure correctness.

New Hampshire’s two delegates to the Convention are the subject of the first essay. The second essay explains the four-month process by which the framers carved out agreement on the terms of the new Constitution.

Essays

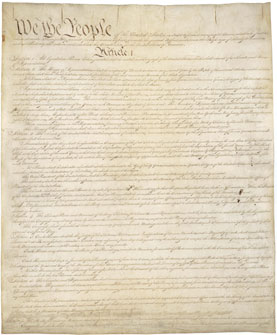

We the People

“We the People of the United States, in order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.”

This famous preamble to America’s governing document summarizes the essential purposes of the Constitutional Convention of 1787. Eleven years earlier, the nation’s founders had authored the Declaration of Independence, renouncing the authority of the British crown. America’s determined patriots had then endured the severities of five years of war to secure her freedom. In 1781, the thirteen sovereign states had established a “league of friendship,” documented in the Articles of Confederation, which created an intentionally weak central government to avoid the tyrannical excesses of a monarchy. However, the Articles of Confederation soon proved inadequate to guide the young nation through the tumult of economic and military challenges it faced in the years following the war.

Under the Articles of Confederation, Congress had no power to regulate the nation’s economy or to levy taxes to support it. It could not financially support an army. America’s war debts to foreign and domestic creditors remained unpaid, and Revolutionary War veterans’ claims for proper compensation had gone unheeded. The lack of a monetary policy brought about widespread inflation and economic depression. Escalating commercial disputes between the states, armed tax revolts by several states’ farmers and laborers, and persistent military incursions by foreign interests underscored the inherent dangers of the weak central government.

The Constitutional Convention, originally called “for the express purpose of revising the Articles of Confederation,” opened in Philadelphia on May 27, 1787. Delegates from each state except Rhode Island, which declined to participate, were eager to contribute their own perspectives on the Articles’ shortcomings and the best means to correct them. By late June, the delegates scrapped the Articles of Confederation and took on the task of crafting a new governing document that would provide for national unity, stability and defense while still protecting the people’s fundamental rights of liberty and self-governance.

The way forward was rife with challenges for the representatives of the twelve participating states and their competing interests. While the delegates generally agreed that the nation’s political, economic and military well-being necessitated a stronger centralized government, there were great differences of opinion as to the extent of its proposed authority over the states.

To safeguard the secrecy of their exchanges, the delegates conducted all deliberations with the windows of Independence Hall closed and the heavy drapes drawn, despite the stifling summer heat. Ideas contained within the Virginia Plan, the New Jersey Plan, the Hamilton Plan and finally, the Connecticut Compromise, were debated and revisited for nearly four months before the delegates devised a system of checks and balances between the executive, legislative and judicial branches of a national government. A bicameral legislature with both equal (Senate) and proportional (House of Representatives) state representation resolved the contentious issue of apportioning congressional membership. Each slave would be counted as 3/5 of a person. Taxation on the importation of slaves was allowed, but any federal right to prohibit the slave trade was postponed. Further, the plan ensured the states’ rights to control commerce within their own borders, and by inference, to exercise all governing powers not reserved to the national government.

While their best efforts were expended over 115 days of negotiation and compromise, none of the delegates could be sure of the success of the constitutional republic envisioned by their work. Addressing George Washington, who served as the President of the Convention, an aging Benjamin Franklin offered his endorsement with uncertain but hopeful sentiments: “Sir, I agree to this Constitution with all its faults, if they are such.” Some of the original fifty-five delegates objected to the plan; but of the forty-two men still present, all but three signed the proposed document on September 17, 1787, believing they had together achieved “a constitutional system which would … best secure the permanent liberty and happiness of their country,” observed James Madison.

The new plan was to be made law upon nine of the thirteen states’ votes to ratify its terms. New Hampshire’s vote in Concord on June 21, 1788, was the crucial ninth for its ratification, immediately putting the Constitution into effect as the “supreme Law of the Land.” By May 29, 1790, all thirteen states had ratified the United States Constitution.

The first ten Amendments to the Constitution, known as the Bill of Rights, were ratified on December 15, 1791. The founders’ foresight in allowing for amendment insured the adaptability of America’s democratic system to changing conditions over time. The Constitution of the United States, which now contains twenty-seven Amendments, and the collaborative process by which it was fashioned, still serve as a working model for emerging democracies around the world.

Delegates from New Hampshire

New Hampshire’s two delegates missed the Constitutional Convention’s early proceedings due to the State’s lack of funds to pay for their expenses. John Langdon decided to personally bear the cost of the trip for both himself and Nicholas Gilman. They arrived in Philadelphia on July 21, 1787.

At the Convention, John Langdon (1741-1819) was vocal in his support of stronger central governance over matters of commerce, taxation, and the military. He spoke from personal experience. Langdon was a businessman in international trade, and had supervised both the importation and distribution of arms to the Continental Army and the building of warships at Portsmouth. He was active in New Hampshire’s legislature, had attended the Second Continental Congress in 1775, and had commanded a highly trained infantry and cavalry company within New Hampshire’s militia during the Revolutionary War. He believed that a binding union of the states and a strong central government would best ensure the protection of personal liberties, promote economic stability, and provide for the nation’s defense. Following the Convention, Langdon was instrumental in securing New Hampshire’s vote to ratify the Constitution. John Langdon remained a prominent advocate of the constitutional system devised in 1787 throughout his career as Governor of New Hampshire and later as a United States Senator.

Nicholas Gilman (1755-1814) served in both organizational and combat roles throughout the Revolutionary War, achieving the rank of Captain in 1778. As Assistant to the Adjutant General, Gilman’s responsibilities for keeping a force in the field brought him into regular contact with the military leaders of the Continental Army, including General Washington. After the war, Gilman turned to a life in politics, convinced that compromise among the nation’s various factions and interests would be integral to its ultimate success. The day after signing the Constitution of the United States, Gilman characterized it as “the best that could meet the unanimous concurrence of the States in Convention; it was done by bargain and compromise, yet, notwithstanding its imperfections, on the adoption of it depends … whether we shall become a respectable nation, or a people torn to pieces ....” Nicholas Gilman went on to serve in both the United States House of Representatives and the United States Senate.

About the Painting

Howard Chandler Christy

Scene at the Signing of the Constitution of the United States

Dedicated in 1940

Oil on canvas (18 x 26ft.)

United States Capitol Building

In celebration of the United States Constitution’s sesquicentennial, Congress commissioned Howard Chandler Christy to produce this work. This painting represents the thirty-nine signers of the Constitution, assembled together at the Pennsylvania State House (later named Independence Hall) on September 17, 1787.

The artist visited Independence Hall on a September 17th at the same time of day that the signing took place, intending to replicate just how the light from outside would have filtered into the room. He used the soft lines and vivid colors of American Impressionism to create a natural, lifelike scene.

While Christy chose not to include the three delegates in attendance who did not sign, he carefully researched the subjects, furniture and artifacts of the day’s event. To best depict the likenesses of the signers, Christy copied many of their faces directly from original portraits. In some cases, he determined the exact clothes worn by the delegates. For example, the clothes worn by George Washington, including the watch fob in his hand, are exhibited in the Smithsonian Museum.

Eighty-one-year-old Benjamin Franklin is seated, wearing a fashionable blue suit he brought from France. The books under Franklin’s chair were from Thomas Jefferson’s personal collection – an acknowledgement by the artist of Jefferson’s importance to the Constitution despite his absence from the Convention (Jefferson was then serving as Minister to France). The chair used by George Washington, engraved as Franklin observed with “a rising, not a setting, sun,” is also featured.

This painting is one of the United States Capitol Building’s most popular attractions.