12. The Concord Coach

Located: 1st floor hallway, near Courtroom B

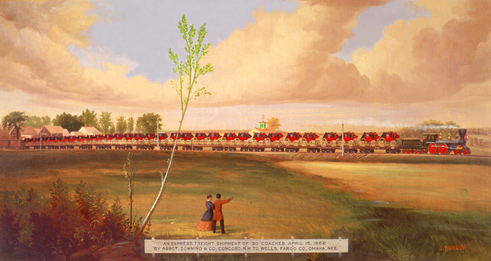

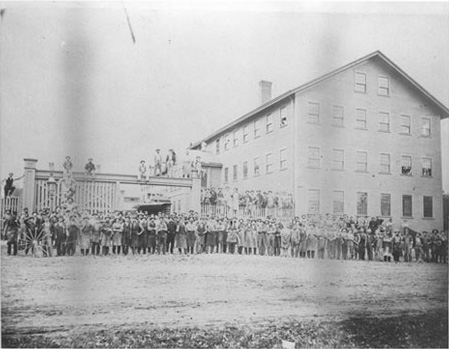

Prints in courthouse exhibit: John Burgum, An Express Shipment of Thirty Coaches, April 15, 1868 (c. 1870); photograph of Abbot-Downing Co. employees; photograph of Buffalo Bill Cody in a Concord Coach (New Hampshire Historical Society)

This painting of a nineteenth-century shipment of thirty made-to-order stagecoaches records the substantial role played by the Abbot-Downing Company of Concord, New Hampshire, in our young nation’s westward expansion. The company was world-renown for its superior design and manufacture of stagecoaches and carriages.

Concord Rolls onto the World Stage

This painting of a nineteenth century shipment of thirty made-to-order stagecoaches records the substantial role played by the Abbot-Downing Company of Concord, New Hampshire, in our young nation’s westward expansion. Wells Fargo & Co., the largest stagecoach delivery enterprise in the world, was just one of many customers around the globe that utilized Abbot-Downing’s Concord Coaches. Pictured here is a freight train with fifteen raised platforms for the new coaches, along with extra cars for harnesses and related cargo, all loaded in Concord and bound for Well Fargo’s base of operations in Omaha, Nebraska.

The manufacturing prominence achieved by the Abbot-Downing Company reflected the innovation, talents and hard work of founder Louis Downing, his partner J. Stephen Abbot, and the several hundred local craftsmen and laborers they employed. Louis Downing had arrived in Concord in 1813, a youthful wheelwright with the skills and ambition to start his own business. In 1826 he enlisted the services of coach body maker J. Stephen Abbot to assist in the building of carriages. For the rest of the century the two men and their sons directed the manufacturing of wagons and carriages, including over three thousand seven hundred Concord Coaches. Each one was designed, built and colorfully hand-painted to order right here in Concord.

The Concord Coach was well-suited for the treacherous duty required of overland express routes. Seasoned hardwood wheels with handmade spokes stood the test of difficult weather and ground conditions without warping. Hand-forged iron bands ensured the strength of the chassis, and iron steps and railings secured the safety of passengers seated inside or on the roof. The Concord Coach’s unique bullhide-braced suspension transformed the typical overland carriage ride from a punishing series of bumps to a somewhat more forgiving sway, aimed at reducing injury to the pulling horses and presumably providing the same benefit to the passengers. The sturdy thoroughbraces held a gracefully curved carriage with fringed cushioned seats, leather curtains, side candle lights and other customized features and ornamentation. Hand-painted landscapes, images and scrollwork added a touch of elegance to vehicles built especially to endure the severity of long and trying journeys.

The exhibited painting, based on a photograph of the shipment, is the work of John Burgum, an Abbot-Downing Company employee whose artwork regularly adorned the passenger doors of the Concord Coach.

Westward Bound

Commandeered by highly skilled drivers and their teams of six horses, Concord Coaches were heavily relied upon for delivering mail, treasure, cargo and passengers throughout the states and territories. Western overland routes were plagued with all the natural hazards expected of a barren countryside, rough terrain and severe weather; presenting a coach ride quite unlike luxury hotel transports in the cities. Nevertheless, people were eager to travel, and the well-reputed Concord Coach offered an exciting means to experience the vast, unfamiliar west. One author’s trip from Missouri to Nevada was vividly described, with some likely embellishment, in a book aptly titled Roughing It:

“Whenever the stage stopped to change horses, we would wake up… and in a minute or two the stage would be off again, and we likewise….[E]very time we flew down one bank and scrambled up the other, our party inside got mixed somewhat. First we would all be down in a pile at the forward end of the stage, nearly in a sitting posture, and in a second we would shoot to the other end, and stand on our heads. And we would sprawl and kick, too, and ward off ends and corners of mail-bags that came lumbering over us and about us; and as the dust rose from the tumult, we would all sneeze in chorus….

“Every time we avalanched from one end of the stage to the other, the Unabridged Dictionary [part of the cargo] would come too; and every time it came it damaged somebody…. The pistols and coin soon settled to the bottom, but the pipes, pipe-stems, tobacco, and canteens clattered and floundered after the Dictionary every time it made an assault on us, and aided and abetted the book by spilling tobacco in our eyes, and water down our backs.

“Still, all things considered, it was a very comfortable night….”

[On crossing the desert:] “[I]magine team, driver, coach and passengers so deep coated with ashes that they are all one colorless color; imagine ash-drifts roosting above mustaches and eyebrows like snow accumulations on boughs and bushes. Two miles and a quarter an hour for ten hours – that was what we accomplished…. On the nineteeth day we crossed forty miles of bottomless sand, into which our coach wheels sunk from six inches to a foot. We worked our passage most of the way across.

“That is to say, we got out and walked.”

- Mark Twain, 1871

Tips for Stagecoach Travelers

When the driver asks you to get off and walk, do so without grumbling.

(He won’t request it unless absolutely necessary.)

If a team runs away -- sit still and take your chances. If you jump, nine

times out of ten you will be hurt.

Don’t growl at the food received at the station.

Don’t smoke a strong pipe inside the coach. Spit on the leeward side.

If you have anything to drink in a bottle, pass it around.

Don’t swear or lop over neighbors while sleeping.

Never shoot on the road, as the noise might frighten the horses.

Don’t discuss politics or religion.

Don’t point out where murders have been committed, especially if there are women passengers.

Don’t imagine for a minute that you are going on a picnic. Expect annoyances, discomfort and some hardship.

Omaha Herald, 1877

A Wild Ride for Notorious Westerners

Californian “Black Bart” robbed twenty-eight Wells Fargo Concord Coaches in his career, sometimes leaving poems such as this one:

Let come what will, I’ll try it on, my condition can’t be worse

And if there’s money in that box, it’s money in my purse.

The infamous Wyatt Earp rode a Concord Coach next to the driver as a shotgun messenger, guarding its treasure box on Arizona silver mine routes.

“Calamity Jane” once grabbed a slain driver’s reins to escape from a stage station, saving the frequently targeted Deadwood (South Dakota) Mail Coach and its six passengers from a fierce Indian attack.

Buffalo Bill Cody later purchased the famed Deadwood Coach for use in his Wild West show. After touring Europe, where royal family members of eight nations were treated to rides in the historic vehicle, Buffalo Bill returned the well-worn coach, still intact on its four original wheels, to Concord for an extravagant show and welcome home ceremony in 1895.

The print, based on a photograph of the actual event, is displayed on the first floor of the US District Court building.